Terry Everman

Terry EvermanAt full power, DOCKHOUSE QUEEN scoots along at 7 knots.

Terry Everman grew up in a Columbia River tugboat family, and after a 30-year career in the shipbuilding industry, he built a tug for himself. It wasn’t big, like the tugs that he’d seen as a boy, but it was the biggest tug he could build in a one-car garage. He had gathered experience building other small wooden boats: 8′ MiniMax hydroplane, Phil Bolger’s Cartopper, Warren Jordan’s Baby Tender (a cradle boat), Mac McCarthy’s Wee Lassie, and a traditional Melonseed skiff.

Genie Cary

Genie CaryThe curved stern was difficult to construct but has the right look for a tug.

The mini-tug started with measuring the garage that would be Terry’s workshop. A length of 16′ would leave him some room to get around the ends, and the 7′4″ beam left just 1″ of clearance on either side to get through the garage door. He began working up the design on a basic computer program. His friend Harry Schoenauer lent a hand fine-tuning the design before building began.

Terry Everman

Terry EvermanThe rolling building platform and the roll-over frame were sized to get through the garage with only 2″ to spare.

After a year devoted to designing the tug, the first project was to build an 8′ x 16′ rolling platform so the hull could be moved outside when it came time to roll it upright. Shaped panels of marine-grade plywood—½″ on the bottom, two layers of ¼″ below the side rail, and ¼″ for the bulwarks and house— gave the tug its shape. The rounded stern was essential for the classic look but a challenge to build. Thickened epoxy fillets strengthened the joints, and sheathing of 7-oz fiberglass cloth with epoxy reinforced and protected the hull. Empty spaces below the deck were filled with a poured-in foam mix for flotation. When the hull was finished, Terry and friends pulled it outside and rolled it over, and then pushed it back into the garage. The tug’s house was built in a separate garage and later set on the hull.

Terry Everman

Terry EvermanThe spaces between frames below deck were filled with poured foam for flotation.

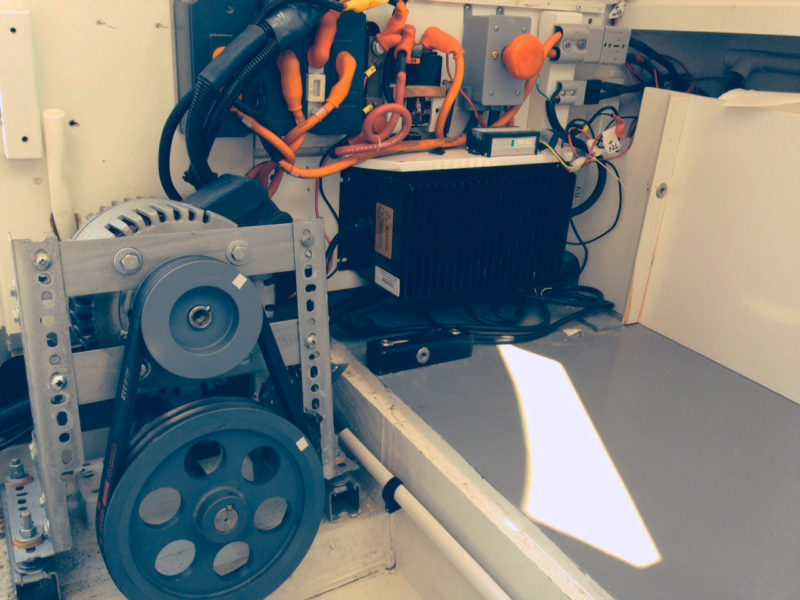

Back in the garage, the tug was given its power plant, a brushless electric motor (72V, 350A) from Electric Motorsport. Powered by six 12-volt deep-cell marine batteries, the motor would produce the equivalent of 31 hp. A 14 pitch x 10″ propeller is driven through a 2:1 double V-belt reduction. The keel added to the V hull to protect the shaft and prop brought the tug’s draft to 24″.

Terry Everman

Terry EvermanThe electric motor sits above the drive shaft and is connected to it with a 2:1 double V-belt reduction drive.

Terry built DOCKHOUSE QUEEN in south Florida and completed construction in two years. He and his wife Sandy then towed the tug to their homeport in Cathlamet, Washington. The cross-country trip drew lots of compliments: people enjoyed the unique cartoon character of the boat. DOCKHOUSE QUEEN performs as Terry expected for a vessel with a sheer plan shaped like a watermelon and a one-ton displacement. At a minimal effort of 30 amps, she makes 4 knots. Top speed with a 150-amp draw is 7 knots. At a casual cruising speed of 3 to 4 knots, the batteries will provide power for several hours. “A quick charging session,” says Terry, “and she is good to go. No fueling fumes, messy bilges, or fuel-dock credit cards.” Terry entered DOCKHOUSE QUEEN in Cathlamet’s yearly Wooden Boat Festival, and she was awarded First in Class.![]()

Afterword

Terry Everman passed away unexpectedly just two months after this issue was published, and now DOCKHOUSE QUEEN is in need of new owners. Please email me if you’re interested.

Christopher Cunningham, Editor

In the comments below, Ed was interested in hearing more about the rolling platform. Terry replied with photos and details:

The platform frame

The platform with decking in place

Platform at the start of construction

After roll-over, the hull and frame rest on dollies.

Rolled back into the garage on dollies, the boat is a tight fit in the workspace.

Having grown up in New York, I have always been a fan of tugboats—they are the workhorses of the harbors. It was a treat to read about the DOCKHOUSE QUEEN and even more fun to look at the photos. Terry did an excellent job in caricaturing the unique features inherent in classic tugboats and it certainly has a cartoonish quality that is just simply appealing. It made me smile. Thank you!

Fantastic build. This was the first story I read in this issue. I am interested in electric-powered boats of any kind. I keep reading Electric Propulsion for Boats by Charles Mathys for information and inspiration but your one photo of the power plant is very much appreciated and helpful. Enjoy your tug!

Beautiful job, Terry. Love the stern—Popeye would be proud.

I’m getting ready for my own in-garage build and have shifted my focus to the rolling platform. I’ll likely build two so I can roll it onto another one and slide it back in without having to reposition it on the platform construction started on. I’m still thinking it through. Any lessons learned with your rolling platform?

Terry provided some additional information on the platform along with some more photos. That’s now added to the article above.

Christopher Cunningham, Editor, Small Boats Monthly

Great build Terry! I too am interested in the electric propulsion. More details would be appreciated. I am on a shallow lake and would like to build a launch with electric propulsion and a Seabright type hull.

Pat, the selection of electric propulsion was fun and exciting but several considerations should be addressed. I used a kit from electricmotorsport.com and was very satisfied with their service and the motor kit, the electric equivalent 31 HP motor yet weighing just 28 lbs— quite impressive. The six deep-cell 12-volt batteries, however, were economical but weighed nearly 400 lbs. A 48-volt system could weigh around 260 lbs. More sophisticated batteries—AGM or lithium-ion—would reduce the weight significantly, but the cost, in my case, was prohibitive. The added weight of the lead-acid batteries I use might be a deal breaker on a narrower boat.

The electric propulsion system was simpler to install than an internal combustion workhorse—there were no fuel tanks, oil, cooling, or exhaust systems to consider—but you are always aware of the remaining charge in the battery bank and how far you can travel away from the recharging umbilical cord.

In my case, the construction decisions were for my interests and an opportunity to scratch the various itches spinning in my head. Building a boat can satisfy that itch, possibly unique to the individual, and keep the adrenalin pumping. Good luck on your Seabright, I also am a fan of that type of small boat.