What was left of the boat rotting in the brambles on the north shore of Clear Lake in Western Washington was once a very fast boat under oars. Back in the 1930s John Thomas “could row it across the lake, fill up two gallon jugs with spring water and row halfway back on one cigarette.” When John Sack, Thomas’s nephew, took over the lakeside family cabin in the 1960s, the boat had been sitting at the base of the largest pine tree on the property, unused for a decade.

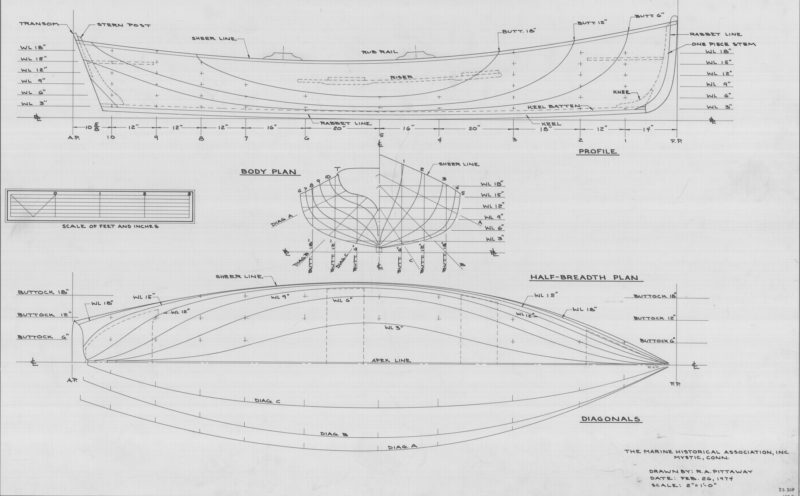

In 1983 John asked me to build new boat to replace the one his uncle had thought of so highly. Rot had taken a heavy toll and although most of the sheerstrake was gone there was enough boat there to measure it and to show how it was put together. My search for the origins of the boat led to the lines of a lapstrake Whitehall Livery Boat in Maynard Bray’s Mystic Seaport Museum Watercraft. The shape, dimensions and many of the construction details—shortcuts for an easy, quick build—were a nearly perfect match. Bray writes: “…in spite of the quick and dirty way she is built, there is nothing at all second rate about her shape; she is one of the nicest modeled puling boats in the entire collection.” I ordered the plans and set to work.

Photos and video by the author except where noted

Photos and video by the author except where noted“There is nothing second rate about her shape; she is one of the nicest modeled pulling boats in the entire collection.”

The livery boat is 13′6 ⅝″ long with a beam of 3′7 ½″. It has seven strakes and steam-bent oak ribs on 5 ½″ centers, clench-nailed at the plank laps and riveted at the gunwale. The last two frames at either end take very tight turns at the keel, so supple bending stock is a must.

The keel and the keel batten (as they’re labeled on the plans) run nearly straight from stem to sternpost. There is no deadwood forming a skeg as on some Whitehalls, so the garboards, rather than turn upward to the transom, follow the keel and batten and twist to vertical at the sternpost, much they would in a double-ender.

The plans note that the boat has a one-piece stem. I’d be surprised if that were indeed the case. The aft end of the garboard and broad strakes run past the sternpost and are capped with a small triangular false sternpost, fastened after the planks are trimmed flush. The forward end of the garboard in the relic I saw has an odd jog around the outer stem (a detail that isn’t clear in the plans or the photograph in Bray’s book) that suggests the use of a false stem.

Lightly built, the livery boat makes rowing a pleasure.

The plans indicated that the garboards were run past the keel batten and then planed flat to accept the keel in the same manner that a dory’s garboards are planed flush with the bottom and protected by a false bottom. With rabbets and the time they take to shape eliminated from the stern and keel assembly, it seems unlikely that the stem would be of one piece and rabbeted to accept the hood ends of the planks. I built John’s boat with a two-piece stem.

Bray notes: “…what appears to be the keel is in reality only a chafing strip to protect the garboards from damage. Thus built, the garboard seam is hidden and cannot be caulked later.” To avoid problems with the seam between the keel and the garboard, I widened the keel batten, and the garboards overlap it much like any other plank lap for most of their length. With the oak keelson resting mostly on the oak batten for much of its length, it has a more solid footing than it would on the feathered edges of soft cedar planking. The 3M 5200 I used in the seams has kept the laps at the keel and the rest of the hull tight and leak-free for 31 years.

The boat is, as you might expect of a fast pulling boat, a bit tender. I can stand in it with confidence, but stepping upright from one thwart to another gets a bit twitchy. The stability picks up quite quickly so it doesn’t twitch far, but I prefer getting aboard or moving about with my hands on the gunwales. Seated, of course, the boat is comfortably stable. When I sit at the side of the center thwart, my 200 lbs bring the sheerstrake to the water’s surface.

The frames in very ends of the boat take some very tight turns. Better trim could be achieved with a passenger aboard by making the stern bench longer and adding a backrest to put the additional weight farther forward.

There are two rowing stations but a boat this size doesn’t gain anything by having two people at the oars—more power won’t make it go appreciably faster. One station is for rowing alone and the other for rowing with a passenger in the stern. The volume of the stern sections is carried quite high, so it’s best to have the heavier occupant at the oars. With John in the stern sheets and his daughter Mary at the oars, the boat settled down by the stern. Had they changed positions the boat would have trimmed well. The thwarts are set just 5 ½″ below the sheer, so the oarlocks are set in pads that add another 2″ of height for more clearance for rowing.

The plans call for thwart knees sawn from straight-grained ¾″ stock, certainly the simplest solution to bracing the hull, but I opted for bent knees for a less clunky appearance and adequate strength for the boat’s purpose. Simple blocks of wood secured to the center floorboard provide foot bracing adequate for casual rowing.

The hull’s very fine waterlines aft and ample drag keep it tracking arrow straight. If I were to build the boat again I might move the thwarts 6″ or 8″ to have the stern settle not quite so deep. For now, any cargo, like John Thomas’s gallon jugs of spring water, would serve the trim best when set in the bow.

The short waterline length makes the livery boat easy to maneuver. Changing course while underway takes few strong pulls on side, and at a standstill I could spin the boat through 360 degrees in 10 strokes, pulling one oar and backing the other.

For Mary Sack, John’s daughter, and her two brothers, rowing has been one of the pleasures visiting the family cabin on Clear Lake.

With a lazy pull at the oars I could poke along at a GPS-measured 3.5 knots and go almost as fast backing. A little more effort took me up past 4 knots. I peaked at 4 ¾ knots, about what I’d expect for a waterline length of just under 13′. Not being a smoker I didn’t try to see if I could get across the lake and halfway back on a single cigarette. At speed the wake’s transverse waves are small; there is no gurgling coming from the stern as the boat eases the displaced water back together. The boat carries well between strokes. The hull is light enough that when I swing my upper body aft during the recovery, the boat surges ahead.

Mary Sack

Mary SackAt a relaxed pace the livery boat is easily driven. Here, pushed hard, it does around 4¾ knots.

John, a devotee of racing shells, equipped the boat with folding bronze outriggers that increased the span between the locks by 13″. The arrangement worked well enough with his 9′3″ racing sculls, although the boat won’t go any faster; rather than increase the speed, the longer oars just lower the rowing cadence and for some, that’s a more pleasant way to row. The outriggers have sockets for the original rowlocks so the boat could still be rowed as designed, on the gunwales, with the 7′3″ spoon-blade oars I built for the boat. The shorter oars offer the higher cadence I prefer and more clearance over the legs for the stroke’s release and recovery. The clearance for the stroke was good for flat water I’ve had on the lake whenever I’ve rowed John’s boat, but there’s enough freeboard and enough clearance for the oars to take on the kind of chop a small lake is likely to generate when the wind comes up.

This boat is not a workhorse. Only 15½″ deep amidships (13¾″ measured inside), it hasn’t an abundance of freeboard for rough water or carrying heavy loads. Bray surmised that the design was for a boat that “might have been kept by a lakeside summer hotel for use by its guests.” The boat I built for John, like the boat his uncle took such pride in, was ideally suited to his lakeside cabin.

The plans from Mystic Seaport are on three sheets: lines drawings, a table of offsets, and construction details. If you’re unfamiliar with traditional lapstrake construction there are good books to guide you through the process—Walter Simmons’ Lapstrake Boatbuilding and Greg Rössel’s Building Small Boats, to name just two. Some of the “quick and dirty” details of the livery boat’s construction can actually fare quite well with today’s modern adhesive sealants, eliminate some fussy and time-consuming tasks, and get you on the water faster.![]()

Christopher Cunningham is the editor of Small Boats Monthly.

Particulars

[table]

LOA/13′6⅝″

Beam (inside planking)/3′7½″

Depth/15½″

[/table]

© Mystic Seaport, Daniel Gregory Ships Plans Library

© Mystic Seaport, Daniel Gregory Ships Plans LibraryPlans are available from Mystic Seaport. The accession number is 1973.728 (formerly listed as 73.728).

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!

The stem, if made from a natural crook or knee, could very well have been of one piece.

A crook with the appropriate curve could indeed be used to fashion in one piece what the boat I built, but the old livery boats of Mystic Seaport (photos of the original shown here) and Clear Lake had three pieces: stem, false stem, and knee. While crooks might have been more readily available when the older boats were built, they still could have added significantly to the construction time. Selecting a knee with the right sweep of grain, curing it, and milling it would slow the production of boats built in great numbers. Dried straight-grained lumber was and is easy to come by and cutting a knee to join the stem to the keel needs little more than a sharp pencil line and a sure hand on the bandsaw. The two-piece stem with inner and outer halves doesn’t require mapping out a rabbet and cutting it with a chisel and mallet. The bevels on the inner stem might not even need to be transferred from patterns or lofting: battens sprung around the molds would quickly indicate where wood needed to be pared away and when the correct bevel was attained. After planking, the ends of the planks get trimmed and the outer stem goes on. Anyone who decides to build the boat can choose how to construct the stem. The one-piece crook would be elegant and very strong; the three-piece construction would be a lot faster.