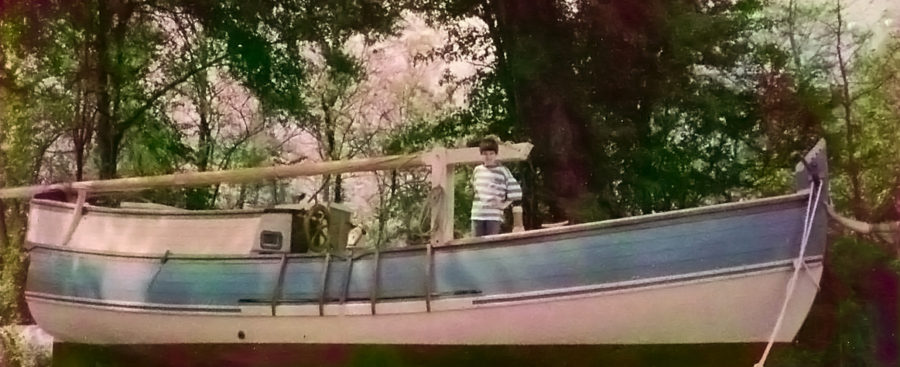

When my parents returned home to Edmonds, Washington, from a trip to England in 1983 they brought me two green booklets about the Gokstad faering, the smallest of three ninth-century boats unearthed along with the Gokstad ship in 1880 near Norway’s Oslo Fjord. The 21′ faering was the most beautiful boat I had ever seen, and I wanted to build a replica of it. I was 30 and I’d been building boats for five years, sometimes for hire, sometimes on a whim. I waited for an opportunity to build the faering, and getting married provided it. Cindy and I were married in the summer of 1986 and we put off having a honeymoon while she finished grad school. I was self-employed, building and restoring boats along with working on a llama farm on Lopez Island in the San Juan Islands of Washington State. She would finish school the following spring, so I hatched a plan: I’d build the faering that winter and in the summer of 1987, we’d take a honeymoon cruise, rowing the Inside Passage from Washington to Alaska. I went to work on the boat in a temporary shed in my parents’ back yard not far from Puget Sound.

photgraphs are either by the author or from his collection

photgraphs are either by the author or from his collectionCarving the stems was by far the most difficult task I’d faced as a boatbuilder. It took me a week just to figure out how to start the job, and another three weeks to finish it.

I was so eager to see what the boat was going to look like right side up that I hung by my knees from a ladder to get a sneak peek.

When I finally got the faering out of the shed, my father (left) and I admired the Viking form from every angle.

I didn’t finish the project as quickly as I had planned, and the day the last coat of varnish dried was the day we launched the boat and started our row to Alaska. About 40 people attended the launch at a beach near the Mukliteo ferry dock. There was a launch ramp at the beach, but instead of backing the boat into the water on the trailer, ten of our friends lifted the faering to their shoulders, carried it across the cobbles, and set it gently in the water.

It was fitting to have the faering, built to a design over 1,100 years old, carried by hand to the water for the first time.

We christened the boat ROWENA, after the wife of Ivanhoe in Sir Walter Scott’s novel. Cindy and I took the first few strokes and I saw the boat was taking on water. I traced the leak to a pitch pocket in one of the garboards and did a quick patch with 5-minute epoxy and added duct tape inside and out. That seemed to do the trick and kept the boat dry while many of our friends took turns rowing the faering.

Soon after we took the first few stroke in the newly christened ROWENA, we discovered a leak in a garboard.

When we started putting drybags aboard to get ready to depart, it was clear that we had too much cargo and there was barely enough room left for us to squeeze in. As Cindy and I got underway, a bagpiper started playing; a newspaper photographer’s camera, clicking away with a motor drive, was buzzing like a cicada; and above all the racket and the applause of our friends, I could hear water sloshing beneath me. Soon it was rising up through the floorboards. We would have to get ashore and fast. We had gone only a hundred yards, and I couldn’t imagine turning back. A ferry was on its way to the dock, and it would soon pass between us and the crowd of waving well-wishers on the beach. Cindy and I maintained our course—north to Alaska—until the ferry blocked us from view and then we made a quick turn west toward the beach at the north side of the dock. As far as our friends knew, we were well on our way, over the horizon and swallowed up by distance. All but one. Archie knew that we should have been visible for miles. He told my parents something was up and the three of them drove around to the beach on the north side of the dock and found us there, bailing.

We hauled the boat out, privately, back at the ramp and took it to Archie’s place just up the road. Cindy and I, exhausted by the long hours we’d spent getting ready for the launch, took a four-hour nap. When we got up, we sorted through all of our gear and repacked the essentials.

The real start to the journey began in Anacortes with just my mother and father to see us off. We had culled a lot of excess gear, so ROWENA wasn’t so chock full of dry bags.

The following morning my Mom and Dad drove us to Anacortes, where we launched again without fanfare under a haze-softened sky. We rowed west across Rosario Strait, potentially a dangerous 3 1/2-mile crossing to the San Juan Islands, but very little tide was running and the water was merely scuffed by the breeze. We made good time and Cindy, who had never rowed much before, was quickly getting the hang of it. The oars felt heavy in my hands and awkward in the water. I had made them according to the drawings in the books about the Gokstad faering—9′ long with lance-like blades—but ROWENA, with a beam of just 4-1/2′ and heavily laden, sat low in the water, and the oars were way too long. It was hard to clear the handles over our thighs, and the gearing was too high for the load we were carrying. I worked out the standard oar-length formula in my head and decided I’d shorten the oars by 18″ at the first opportunity.

After crossing Rosario Strait we took a break at a small cove on Decatur Island, halfway through Thatcher Pass.

Safely across Rosario, we rowed through Thatcher Pass and pulled ashore at Spencer Spit on Lopez Island. The faering has a keel a few inches deep running the full length of the hull and a moderate V section amidships, so it didn’t take well to being dragged out of the water. We had to tuck fenders under the bilges to keep the boat upright and protect the varnished hull.

When we landed on Lopez Island for our first overnight stay, I was still finishing many of the projects that I’d started before we embarked. With ROWENA was supported with fenders, I put the finishing touches on the canopy.

We left ROWENA to settle on the beach as the tide receded, and set up our tent on high ground. I spent the following day shortening the oars, cutting 18″ off the inboard ends with the folding saw we carried, carving new grips with a crooked knife, and relocating the leathers.

The original rudder was meant for sailing and created too much drag to use for holding course while rowing in a crosswind. We spent another day at a Lopez Island marina, and I carved a slender rudder out of a piece of yellow cedar I found. I rigged a steering system with lines that allowed me to control the rudder with a small tiller on my foot brace.

The shortened oars worked much better as we rowed through the heart of the San Juans. At the end of the day we pulled into at Neil Bay, a narrow half-mile long inlet at the north end of San Juan Island. It was our first time spending the night aboard and Cindy and I hadn’t yet acquired the reflexes to move in harmony to keep the skinny faering upright, so we were regularly loosing our balance and rocking the boat. We pulled the floorboards up and set them across the risers. (The original faering didn’t have risers; I installed them when I realized that the floorboards would be roughly the same length as the thwarts and could be used to make a sleeping platform.) I set the three fiberglass tent poles in the holes in the sheer while Cindy unrolled the extension of the fabric foredeck that would enclose our covered-wagon-inspired sleeping quarters.

The canopy was a simple affair and a bit saggy, but it made a great refuge. We could get away from rain, cold, and bugs. We often set the stove just outside the flaps that closed off the aft end, and had our meals “indoors.”

We had our accommodations ready by dusk. The indigo sky pressed the last of the daylight behind the wooden shoreline to the west and the bay grew still and speckled with starlight.

Finishing the square sail would wait until we got to Nanaimo. A nylon tarp that I’d sewn 16 years earlier for backpacking served as a stand-in for the square sail. The square sail’s yard was pressed into service as a mast and I used the push-pull tiller as the yard.

In the morning we got underway early, rowed north past Spieden Island and shot the 300-yard wide gap between Stuart and Johns islands, fighting the ebb tide. The 4-mile crossing of Haro Strait to the Canadian Gulf Islands is subject to strong tides and lots of ship traffic, but we got across quickly and without any trouble other than sunburned knees (we hadn’t yet found our sunscreen). We rowed into Bedwell Harbor to clear customs. Cindy stayed aboard as I walked up to the office overlooking the dock. When I told the agent we were checking in after crossing from the San Juans, he looked out the window, and the only boat he saw was our faering. “Where’s your boat?” he asked. “That’s it,” I replied, pointing at ROWENA. “No, where’s the big boat you made the crossing in?” “That’s it. We’re on our way to Alaska.” This extra bit of information only added to his consternation, but he cleared us and we went on our way.

We needed a place to stay in Nanaimo while I got a toothache taken care of. The couple who owned the property we camped on were much more welcoming than their sign would suggest. The patchwork tent was one I salvaged from the manufacturer’s dumpster. It had been slashed to discourage employees from wandering home with slightly defective products, but a with a little sewing I’d made it functional again.

My sunburned knees weren’t the only things bothering me. I had started the day with a toothache, and it wasn’t getting any better. I toughed it out as we made our way north to Nanaimo. We found a place to come ashore, a beach in front of a private home, and got permission from the owners, Fred and Ethel, to stay as long as we wanted. We made camp next to a No Trespassing sign that was larger than our tent. The pain woke me in the middle of the night and I lay awake waiting for daylight. That morning Fred drove us to town and dropped us off at his dentist’s office. Two hours and one root canal later, I was as good as new.

We spent the rest of the day back at camp catching up on our to-do list. I had sewn the square sail and made the mast before we had launched ROWENA, but I hadn’t rigged them yet. On the beach I made a mast partner out of a yellow cedar 2×4 Fred gave us, whittled cleats, and cut and whipped lines for sheets and a halyard.

The following morning, while Cindy started packing the boat, I ran up to the house to say goodbye to Fred and Ethel. She was in a pink bathrobe already on her way to see us off. Fred was his pajamas, chasing a deer out of his yard. Their neighbors also arrived at the beach to see us off.

We had a bumpy ride in the chop kicked up by a northwest wind and angled out from Vancouver island on a 3-mile crossing to the Ballenas Islands. We came ashore on a rocky beach on the north island and pushed ROWENA back out using a Tsimshian anchoring system to keep her afloat while we explored ashore. The island was thick with arbutus trees with rust-red bark peeling back to reveal smooth new pea-soup green bark underneath. The lichen covering the rocks was so thick and dry that it crunched when we stepped on it, leaving inch-deep footprints. From the top of a knoll we had a good view across the Strait of Georgia. The water was dark blue, scuffed by the wind, but there were no whitecaps. We’d have an easy time on the 5-mile crossing to Lasqueti Island and the following 3-mile crossing to Texada Island.

The wind faded during the crossing, so we skipped Lasqueti and headed for Texada. We rounded the island’s rocky southern tip and rowed another mile and found a powerboat at anchor at the mouth of Anderson Bay. Its skipper called out to us, “You’re just in time for oysters for dinner,” and pointed into the bay.

We would have been happy enough with our dinner of oysters, but the pearls we found in them made for an unforgettable meal.

There were indeed oysters on the tide flats. Cindy picked a meal’s worth while I anchored ROWENA and we soon had the harvest roasting on the stone ring around a campfire. The oysters opened as they warmed, and we ate them straight from the shells, pausing occasionally to spit pearls the size of BBs into our palms.

The skies were clear the following morning, and we packed without having breakfast to take advantage of the fair weather. We rowed out of the bay, rounded the point, and headed northwest along the 30-mile-long east coast of Texada. The wind was from the southeast, funneling between the island and the mainland, perfect for sailing, so I stopped rowing and tied the new mast partner in place across the middle frame. With the mast raised and lashed to the partner, I hoisted the square sail and made the halyard fast to the stern as a backstay. I’d made the Viking-style side-hung rudder shown in the Gokstad booklet drawings, but this time I steered with an oar over the stern. The boat picked up a little speed, but the sail bellied forward and narrowed the span of the foot. Cindy set up the push rod for the tiller as a whisker pole for the starboard clew; the sail spread wide and we took off.

I set a course down the middle of Malaspina Strait. Running downwind, the apparent wind was quite gentle and warm and lulled Cindy to sleep in her nest of drybags in the bow. We sailed 21 miles before the wind shifted around to the northwest; we dropped the sail and rowed the last few miles to spend the night at a marina at Powell River.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

In the days that followed we continued north with overnight stops in the Copeland Islands and the Rendezvous Islands. Six miles north of the Rendezvous group sits Yuculta Rapid, and another 6 miles beyond that Dent Rapid—dangerous passages that we’d have to time just right to avoid getting caught in a chaotic rush of the tides.

With her mast raised, ROWENA had a undeniable Viking look. I never tired of the boat’s elegant form, and was continually impressed at how well it performed.

We left the middle island of the Rendezvous group and rowed in the rain and chop three quarters of a mile west to the steep, thickly forested eastern flank of Read Island. We turned north, crossed White Rock Passage to Maurelle Island and took advantage of the back eddies to work against the south-flowing flood. Every half mile or so there was a bald eagle looking down on us from a perch high overhead. We crossed Hole-in-the-Wall, the 1/5–mile gap between Maurelle and Sonora islands, and pulled into a cove over a mile short of Yuculta Rapids. We were an hour ahead of schedule for the slack tide.

When our time came, we headed north, passed through a momentarily tranquil Yuculta at slack, and rounded the corner at the Sonora Lodge, a discordant cluster of well-appointed buildings surrounded by treacherous waters and inhospitable shores. Many of the submerged rocks we passed over close to shore were covered with mussels no larger than our fingertips and so densely packed that they looked like black velvet. The ebb had begun flowing north just as we reached Devils Hole at the entrance to Dent Rapid. The water gently swirled and boiled around us, but there wasn’t any of the whitewater violence that would develop in the next few hours. Dent Rapid wasn’t going to give us any trouble, so Cindy fired up the stove and made miso soup while ROWENA spun lazily in the nascent whirlpools.

The notorious Dent Rapid would be a much more dangerous place in a few hours, but as we drifted through on the ebb we took a break for hot soup.

After getting safely across Dent Rapid we treated ourselves to a cabin and hot showers at a lodge by Cordero Channel.

We rowed west along Cordero Channel, spent the night at a floating lodge, and spent all of the following day rowing in the rain until we reached Helmcken Island in Johnstone Strait. There was a slender notch in the east end of the island where we could keep ROWENA centered over deep water with 140′ of line spanning the cove.

Our camp on Helmcken island was a bit damp, but there was a quiet cove for ROWENA and and soft mossy perch for our tent.

The trees on the island were second or third growth, spindly compared to the arm-span-thick red-cedar stumps that were scattered in the woods and still bearing the notches loggers chopped for the springboards they used to make their cut above the broad flare of the trunk at ground level. We set the tarp over a small mossy spot to make a place out of the rain for the tent. We had plenty of dead wood around camp to make a fire hot enough to dry our sodden clothes, melt a plastic cup, and scorch one of Cindy’s wool socks. The fire was still smoldering in the morning, and we cooked pancakes over twigs poked into the embers.

Our campfire on Helmcken gave us a chance to warm up and dry out rain-dampened clothes. We didn’t bother chopping up the mostly red cedar driftwood; we just fed the ends into the fire as they were consumed.

We fought against wind and tide in Johnstone Strait and after 5 miles decided it wasn’t worth the effort. We turned east around the tip of Hardwicke Island and retreated up Sunderland Channel too the first refuge we could find, a narrow inlet around a creek.

Johnstone Strait was too rough so we looped around to the north side of Hardwicke Island. The only safe haven was this inlet that was itself quite choppy. The stick stuck upright in the sand marks the level of the water when we arrived. We waited for the high tide the next day to get back under way.

Johnstone Strait was just as bad the next day and we covered only 8 miles and stopped at Port Neville. The following day, after struggling another 10 miles along the Strait, we decided to take an alternate route that looped north around the east end of Cracroft Island. The turn into Havannah Channel put the wind behind us, so we raised the mast and used our nylon tarp as a spinnaker. We sailed about 5 miles, rounded the east tip of Cracroft, and had to fight once more, rowing into chop and a headwind. By the end of the day my armpits were chafed raw.

One of the beams that once supported the roof of a longhouse still had the beautifully carved wolf’s head on one end.

We spent that night at Minstrel Island and the next day stopped at the ruins of Mahmalillikullah on Village Island. (The descendants of the First Nations people who inhabited the village live elsewhere, but the land still belongs to the band. Permission should be obtained before landing. At the time, we were unaware of the courtesy that is called for when visiting sites like this.) A totem pole with the fin of a killer whale still stands, rising above the brambles that had swallowed up the village site. The posts and beams that once supported a longhouse still stand. They had been cut from logs nearly 3′ in diameter and carved with a distinctive pattern of adze-cut grooves. We left the village, and that evening anchored among the islets of the Indian Group.

With the last of the daylight we got ready to spend the night by one of the islets of the Indian Group, 1-1/2 miles from Mahmalillikullah.

Our route took us out into Queen Charlotte Strait, a 14-mile-wide body of water that extends from the cluster of islands we’d been traveling through to the Pacific Ocean. As we had expected, the going got rougher. Rowing up the mainland coast on the north side of the Strait we encountered 25-knot headwinds and a confusion of waves reflecting off the rocky shores. As we fought our way to Blunden Harbor we noticed water sloshing under the floorboards. It was the first time we had taken on a significant amount of water since launching, and I was concerned that all of the pounding in the waves might have split a plank. I checked the aft half of the boat and found no damage; Cindy checked the bow and reported that the hull was intact but water was dripping from the gear tucked under the foredeck. Fortunately, the water was coming over the sheer, not through the hull. The fabric deck was snapped to the outside of the hull and as ROWENA drove through waves, water that would have otherwise flown away from the sheer was slipping under the cover and coming aboard. I was relieved that the boat was holding up to the beating we were taking and impressed that this 1,000-year-old design was so seaworthy.

The wind strengthened and we had to claw our way into Blunden Harbor. This half-mile-wide haven was rimmed with tall trees, but we weren’t able to rest until we had tucked into the lee right up against the shore. The beach we landed on was brilliant white, a midden of sun-bleached oyster shells that crunched loudly underfoot. We unsnapped the foredeck and took all of our gear out. A lot of things had gotten wet, including our change of dry camp clothes and the bag holding our ID and money. Cindy got started with dinner while I lined the bow with the plastic tarp and did laundry in my improvised wash basin.

There wasn’t much left of the old village at Blunden Harbor. The logs sticking out from the bank are the posts and beams of a fallen longhouse. The beach is composed almost entirely of shell fragments, the detritus of thousands of years of habitation. Scattered among the shells we found fragments of glazed pottery and glass trade beads.

This was the low point for Cindy. Queen Charlotte Strait had been hard going, and she was exhausted and discouraged. We talked over dinner and I assured her that the important thing was not to get to Alaska, but to enjoy the time we were spending together. If the voyage had ceased to become worth the effort and the discomfort, we could go home. Knowing she wasn’t obligated to keep rowing , and that she had the power of choice, seemed to make a difference.

During a midday break at Allison Harbor, I relaxed while lunch warmed on the stove. We had a short day prior to rounding Cape Caution, so we had time to dawdle.

We continued working our way along Queen Charlotte Strait, coming more under the influence of the Pacific with every mile. Shelter from the wind was harder to find and ocean swell prevented us from keeping close to shore. Cape Caution, marking the outer limit of the Strait, was going to be the most exposed part of our trip. To get around it we had to pick our moment carefully. We ducked in behind Bramham Island and rowed 2-1/2 miles to a small bay on the mainland side where we would wait for an early-morning attempt on the Cape. We had the rest of the afternoon off so I napped and Cindy read. In spite of the risky passage ahead of us, we were in good spirits. It seemed Cindy’s misgivings about our adventure had evaporated.

We spent the night aboard ROWENA and woke to the alarm clock at 4:30 a.m. Getting moving at that hour was hard, but we were ready to row in just 45 minutes. We headed down Slingsby Channel in a foggy calm; the reflections of the trees along shore reached right up to the boat. We rowed the 5-mile length of the channel and stopped at the entrance to see what was in store for us.

On our way out of Slingsby Channel we stopped at a small waterfall to replenish our supply of fresh water. When we got water from streams we just looked for fast-moving water and didn’t filter or treat it. We never suffered any ill consequences after drinking it.

The weather radio wasn’t picking up any of the stations, so we only had yesterday’s forecast to go by: light and variable winds. The swells were only about 3′ high and only slightly rippled by a light favorable breeze from the southeast. We sat for 25 minutes to see if there was any change in the wind, either in speed or direction. It stayed steady, so we took off for Cape Caution, 6 miles distant. With the wind in our favor we made good speed past Burnett Bay, a 2-mile stretch of tawny sand set between equally long rows of white breakers on one side and silver-gray driftwood on the other.

We had good conditions for a quick rounding of Cape Caution and raced past the light tower, seen here obscured by haze, to get back into more protected waters.

Cape Caution turned out to be a blunt and unremarkable point of land, distinguished only by a squat light tower that was dwarfed by the trees behind it. We still had a lot of ground to cover to get back into the safety of the inland waterways, so we kept rowing at a brisk pace. Four miles beyond the cape we closed in on Milthorp Point, the northward-pointing thumb of land guarding Protection Cove. Cindy spotted whale flukes rising from the water offshore.

As we drew even with the point, I looked over my shoulder to check our course. I saw something that looked like a rock at a first glance, but it was the ridged gray back and twin blowholes of a second whale coming straight at us, just 30 yards ahead. I called, “Way enough,” and we drifted silently forward, waiting. The whale surfaced again directly astern and a few dozen yards away, having passed right under us. We turned the corner into Protection Cove to take a short break. A fisherman at anchor there eyed us as we slipped by, saying, “You just come from Japan?”

Safely around Cape Caution and in among the islands at the entry to Smith Sound, we took a break on a small dumbell-shaped islet. Cindy isn’t doubled over with seasickness here—nausea would get to her a few hours later—she’s looking at shells.

Beyond Smith Sound and Rivers Inlet we were back inside, where we felt much more comfortable with the challenges posed to a small boat. We sailed up Fitz Hugh Sound to Namu, and then took a day off at Bella Bella.

The swells we encontered crossing Smith Sound and Rivers Inlet left Cindy a little seasick. She fell asleep as we approached the Addenbrook lighthouse on our way north into Fitz Hugh Sound.

We timed our departure from Bella Bella to be present at the arrival of LOOTAAS (“Wave Eater”), a 50′ cedar canoe carved in Skidegate by Bill Reid and a team of Haida carvers for Expo 86 in Vancouver, B.C. The canoe was now being paddled from Vancouver 600 miles back to Haida Gwaii (formerly the Queen Charlotte Islands) and stopping at all of the First Nations towns for elaborate ceremonial receptions. It seemed like all of Bella Bella had gathered on the beach. Many of the elders had black-and-red button blankets draped over their shoulders, gleaming with mother-of-pearl buttons sewn on to create animal figures in the Northwest style. LOOTAAS, carrying a team of paddlers wearing white vests, came to a stop a boat length from the beach; the crew raised their paddles, pointed blades skyward.

LOOTAAS came ashore to the enthusiastic welcome of the Bella Bella community. The paddlers in their white vests are lined up at the top of the beach.

One of the crew called out to ask for permission to come ashore; it was granted by a Bella Bella elder on the beach. LOOTAAS was paddled in stern first. The middle section of its hull was painted black; both ends were finished bright and bore bold red and black designs—stylized animals with bean-shaped eyes and rows of rounded teeth. Many of the Bella Bella residents were taken out for short rides, elders first, then children. Cindy was invited aboard for one of the last tours. I had been talking with Ron, the canoe’s steersman, and when the event was winding down, he invited me to come aboard and paddle LOOTAAS to the dock where it would spend the night. Instead of the usual crew of 12 paddlers and the steersman, Ron had just two of us at his command, but we were able to get LOOTAAS moving.

When the welcoming ceremonies were over, I got a chance to paddle LOOTAAS. There were just three of us aboard and we were going stern first, but it was an honor to be aboard.

That afternoon Cindy and I rowed west along Seaforth Channel, and spent what should have been a peaceful night at a well protected anchorage at Beasley Island. In the middle of the night I awoke to Cindy shouting, “Marty, look out!” “What’s up?” I asked, realizing she was in the middle of a dream. “We’re going to run into it!” “What?” I asked. “Do you want me to steer or something?” she replied, in a less-agitated voice as she woke. She didn’t remember much of the dream when I asked her about it. Although she had committed herself to continuing the trip when we left Blunden Harbor, at least some of her anxiousness about it was apparently still with her. I admired the grit she had been showing since Blunden in the face of the daily discomforts and demands of rowing. I never did find out who Marty was.

We had stocked up with enough supplies at Bella Bella that we could bypass Klemtu, a small native village on Swindle Island. We were headed north near along Princess Royal Channel when we heard a rhythmic thumping coming from the haze that obscured the channel leading south to Klemtu. A dark spot emerged from the fog, and we could soon tell by the flash of paddle blades that it was LOOTAAS.

A drummer aboard LOOTAAS kept twelve paddlers working in a precise rhythm.

We kept rowing and when the canoe was about 30 yards astern and coming straight at us, Cindy and I started to sprint. A cry went up from the canoe and the drumbeat quickened; LOOTAAS closed the gap all too quickly. Clearly the modern-day Haida paddlers had inherited the abilities of their ancestors to scare the bejeezus out of hapless mariners on the North Pacific Coast.

We put on a sprint when LOOTAAS drew near, and the crew came charging after us. We were no match for their power and speed.

Halfway up Princess Royal Channel we stopped at Butedale, once a busy cannery set on the hillside of Princess Royal Island. I had stopped here when I first rowed up the Inside Passage seven years earlier. Back then the store at the top of the ramp from the dock was open for business and and even selling ice cream. The store was still standing but Butedale was a ghost town, inhabited by a lone caretaker.

Butedale was going to ruin. A month before we arrived, a caretaker had fallen through some rotten decking and had broken his back.

We were given permission to use one of the houses that had been built for a cannery manager. We found it with the front door unlocked and the lights on. Butedale’s generator was powered by water running down from a lake in a huge black snake of tarred wooden pipe. Even though there was only one resident, the lights, baseboard heaters, and water heaters for the whole village had to be kept on for the generator’s sake. Seeing an abandoned village with all the lights on was strange enough, but not as eerie as the state of the house. It looked as if a family had walked out just that morning. Cups of coffee and bowls of cereal were still on the kitchen table, the closets and dressers were full of clothes, and the kitchen cabinets were stocked. But no one had been here for months and no one was ever coming back.

We took advantage of hot showers but didn’t spend the night in the house. We’d had an invitation to stay with a couple aboard their little trawler; when we got back to the dock, we accepted their offer. The house was just too creepy.

Betty and Tony, our overnight hosts during our stay in Butedale, took a picture of our departure from the deck of their cruising trawler.

Princess Royal Channel led to Grenville Channel, a slender and almost arrow-straight passage 44 nautical miles long and hemmed in by steep-sided ridges from 1,000′ to 2,000′ high. Going with the flow there is essential, and traffic from both ends rides the floods in, arrives at mid-channel at slack, and takes the ebbs out. It took us three days to get through Grenville, anchoring in Lowe Inlet, 14 miles in, and Klewnuggit Inlet, another 11 miles in, and getting up in the middle of the night to take advantage of the tides.

Working with the tides in Grenville Channel required getting up at around 2:00 a.m. and rowing into dawn.

We took a day off at Prince Rupert and resupplied. Refreshed, we left town in the rain and headed for the Alaskan border. Dixon Entrance, at the border between British Columbia and Alaska, was the other exposed stretch of water we were concerned about but it wasn’t as risky as Cape Caution; there were a number of islands and inlets that offered safe havens. After leaving Prince Rupert we spent the night at a dock sheltered in a cove on the south side of Portland Inlet, and the next day had an easy 13-mile row across the border in rolling 4′ swells but otherwise calm conditions. We camped on the east side of 800-yard-wide Tongass Island. This was our first landfall in Alaska, but checking in with customs would have to wait until we reached Ketchikan.![]()

Part 2 of this story is in the April 2017 issue of Small Boats Monthly.

Christopher Cunningham is the editor of Small Boats Monthly.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small wooden boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Thanks Chris, for a great story well told. I’m building an Oughtred ELF design.

Great trip and great story Chris!

Looking forward to the next installment.

Beautiful boat. Nice job. I can study the pictures for a long time, and it satisfies something deep inside me.

Great story. One way to really get to know your new mate….

If you were to build a faering style of boat today, would you build to your own design or another designer’s?

If I were to build a faering today, I’d look for a somewhat larger boat that would be a little more spacious and comfortable at anchor. Rowing performance would suffer, so it wouldn’t be as good for a long trip and quick crossings. That said, I still hold the Gokstad faering in high regard as a cruising boat and I doubt any other faering would give me as much pleasure to look at.

Great story, Chris! I am enjoying it so much. Seeing the photo of the Butedale P.O. in 1986 and knowing that it has been consumed by its isolation in rain and wind is a humbling reminder to me that man proposes and Nature disposes. And, to race LOOTAAS (the Wave Eater)? Damn, that’s an honor. But, “You just come from Japan?” will have me smiling for the rest of the day. That question has it’s own IP history.

Looking forward to next month’s continuation of the trip…

Great story, look forward to part 2. Does anyone have building plans for this boat? Working with a skilled friend, we built Ouughtred’s Elfyn. It is a great boat, but the thought of a 21′ version is appealing.

I don’t know of any plans. Perhaps one of our readers can help. I built my Gokstad faering using the lines drawings and overall dimensions that were published in the booklets by parents gave me. The drawings—plan, profile, and end view—were all published in an illustration the size of an index card. I took a photo of the lines and then put the slide in my slide projector to project the image on a wall. I traced the end view full size, but of course the projected lines were quite wide. I spent a lot of time working on the lofting to get a good representation of the lines. Built in the traditional manner, each of the stems would have been carved from a single piece of wood, but I glued together a stack of three pieces. The garboards would have been carved too to create the twist and some hollow. I just steam bent the garboards. They were, as I recall, about 15″ wide so I had to edge-glue another bit of my 12″ planking stock to get the width.

I’ve built quite a lot of boats since then and I’ve learned enough about boatbuilding to know I that I’d never be able to build a Gokstad faering. It’s a good thing that I built mine when I had ignorance in my favor.

Wow, you were very resourceful and innovative. I really admire the projection scheme. I have seen several Gokstad Faerings at the NJ Scandinavian Festival, but I don’t think any were better built or real-world tested like yours. The Oughtred Faering we built used a lot of clever short cuts, laminated stems and plywood. When we had it in the Brooklyn Norwegian 17th-of-May Parade last year it received a lot of compliments. However several older Norwegian-Americans came over to look at it closely only to say “oh its made with plywood” and “its not a real faering”. It would be something if someone were to publish a more traditional step by step instructions on how to build a “real” faering. We still enjoy ours and I think it handles and behaves like a faering.

Great story, Chris, and such a beautiful boat! Where is it now? Do you still have it? I’m sure looking forward to part 2! It sure brings back memories. I, too, bought copies of the two little green books on the Gokstad Faering, by Sean McGrail (published 1976) and dreamed about building it, though as I was just starting out in boatbuilding I was daunted by those huge stems. Almost contemporaneously, In 1976, a short article was published in the National Fisherman about Niklas Koltri, from Torshavn in the Faeroe Islands, invited to Ballard in Seattle for our Bicentennial Celebration to build a Faeroe Island Fyrramannafar–a six-oared boat (roughly 19′ x 5′), which I think would probably be called a sexaering in Norway. The photos of this boat in the magazine, like the Gokstad Faering, spoke to me as having the ultimate essence of boatness. Mr. Koltri, in his late 80s, cranked his boat out in a week or two, having built several hundred of them over the course of his life. I figured, if he can do it in a couple of weeks, it might possibly take me three or four months. After all, how long could it take to fit together six strakes? So I contacted Paul Schweiss, a boat builder in Tacoma, who had helped facilitate Mr. Koltri’s trip, sourcing lumber and fastenings, etc., who very kindly took photos of the boat for me, with a yardstick in each photo for scale, and also sent paper patterns of the stems, etc. Based on this information, I drew up plans over several months, made molds, and got to work. Two years later, instead of the two weeks that Mr. Koltri took, a fairly close copy of the boat was ready for launching. As I wanted to call myself a boatbuilder and make my living at the craft, I decided to sell it after a few months of use. Eventually the buyer donated it to the Center for Wooden Boats in Seattle, where it stayed for many years. The last time I spoke to Dick Wagner, of the CWB, it sounded as though it may no longer be in their possession; they have many boats and he wasn’t sure. If you or your readers might know of the whereabouts of this boat, I’d very much appreciate hearing from you. I look forward greatly to reading your next installment. Thanks again.

Thanks, John. I’ll be providing an epilogue in the second article with information on the history of the faering after the trip.

I don’t recall seeing your boat in recent years at the Center for Wooden Boats. I know the volunteer who takes care of the boats in the Center’s collection and I’ll ask him about it.

Following with great interest. So glad you are sharing the story with us. Brings to mind my trip up the inside on a Tahiti ketch in 1982, including Grenville Channel and a deserted, though illuminated Butedale.

FYI to John, some years ago I remember a faering type of yellow cedar on the docks at the Center. I don’t know what became of that boat. For sure there is no faering in the collection at this time.