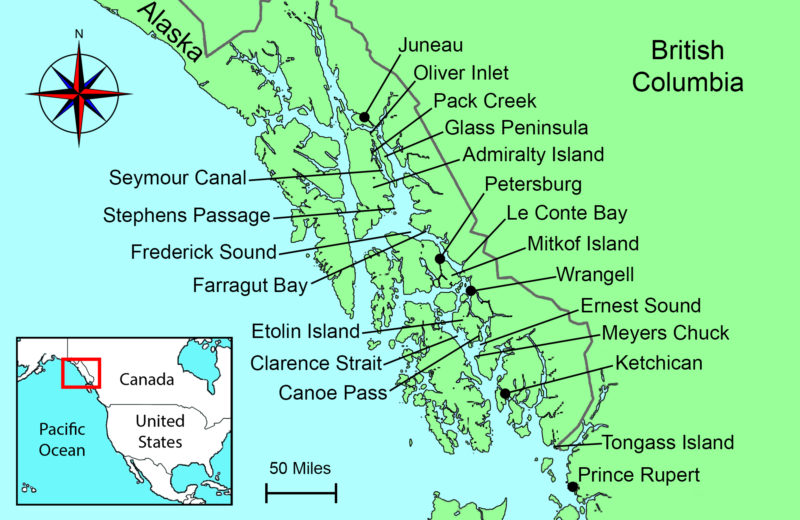

Five weeks into our 1987 voyage from Puget Sound to Juneau, Cindy and I were well into the daily rhythm of life aboard ROWENA, the 21′ Gokstad faering I’d built for the trip. After traveling the Inside Passage through British Columbia we were leaner and stronger, our hands and our butts had toughened up, and we could row long hours, often covering over 30 miles in a day.

Photographs by the author and from his collection

Photographs by the author and from his collectionOur first landing in Alaska was on Tongass Island, the site of a U.S. Army fort in the late 1800s and a native village after that. The only remains of the settlement we saw were fragments of brick scattered on the beach. A heavy rain had soaked our tent the previous night and we spread it out to dry.

Our first camp in Alaska was on Tongass Island, just 6 miles north of the US/Canada border and the site of an Army fort established in 1868, a year after Alaska had been purchased by the U.S. from Russia. The only remnants of the fort and the native settlement that later took its place were fragments of brick scattered among the white-quartz cobbles along the beach. With ROWENA anchored, we took a walk around the island. Cindy found a large yellowed tooth, perhaps from a bear and we saw in the dirt paw prints as big as my hands. I picked up a weathered beer can and filled it with a few pebbles to make a rattle to announce our presence to whatever company we might have on the island. Back at the beach I spread our tent out to dry on the driftwood at the top of the beach—it had rained hard during our last night in British Columbia—while Cindy cooked potatoes, carrots, cabbage and beans for dinner.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

The Tree Point Lighthouse dead ahead faces the open Pacific Ocean. Automated in 1969, it guides mariners across Dixon Entrance. The area can be quite rough, but we had an easy row around the point into Revillagigedo Channel.

We woke to the alarm at 5:00 a.m. and got underway during the morning calm to round Cape Fox, the most exposed promontory at Dixon Entrance. Long fingers of dense fog stretched seaward out from the pass to the south of Tongass Island and from Portland Inlet just beyond the border, but we had good visibility to the north and got around the Cape and the tall white lighthouse at Tree Point with only a northeast breeze and some chop to contend with. Farther north, Revillagigedo Channel was quite calm under clear skies and easy going.

Ketchikan was a nice, quiet town when we arrived.

We arrived at Ketchikan, rowed past the 180′ buoy tender PLANETREE at the Coast Guard station, and pulled in at the first marina we came to. Cindy stayed with the boat while I trotted into town to check in with customs. The agent queried me about my vessel and crew and asked, “Did you have any repairs made while in B.C.?” I told him I’d had a root canal during a stop in Nanaimo.

On my way back to the boat I ran into Tony and Betty, a couple we’d been seeing regularly in ports and anchorages since we first met in Butedale. Their cruising trawler SPIRIT was, of course, much faster than ROWENA, but they stayed longer in the places they visited. They told me they’d be happy to have us spend the night aboard SPIRIT and then went off to arrange for reporters from the local newspaper to interview us that afternoon back at ROWENA.

The following morning we woke aboard SPIRIT, ate breakfast with Tony and Betty, and then Cindy and I walked into town to mail some postcards. Three cruise ships had recently arrived and passengers were flooding into town. The streets were suddenly teeming with throngs of camera-toting tourists. We quickly retreated to ROWENA and cast off.

When we left Ketchikan it was quite crowded. Hundreds poured out of the three cruise ships and the streets were suddenly packed elbow to elbow with tourists.

We rowed north along Tongass Narrows past the row of cruise ships; a woman standing on a dock just to the north of them was waving a newspaper at us. She’d read about us in the morning paper and offered to give her copy to us. The tide was carrying us too fast to get over to her so we could only wave back and shout back our apologies for not stopping. A chop picked up in mid channel so we headed toward smoother water along shore. A man in a T-shirt painting a house rust red yelled, “North to Alaska, wahoo!” A few hundred yards farther along a man stepped out of a house holding up three cans of 7-Up and yelled “Can you use these?” For that we made a U-turn and pulled ashore.

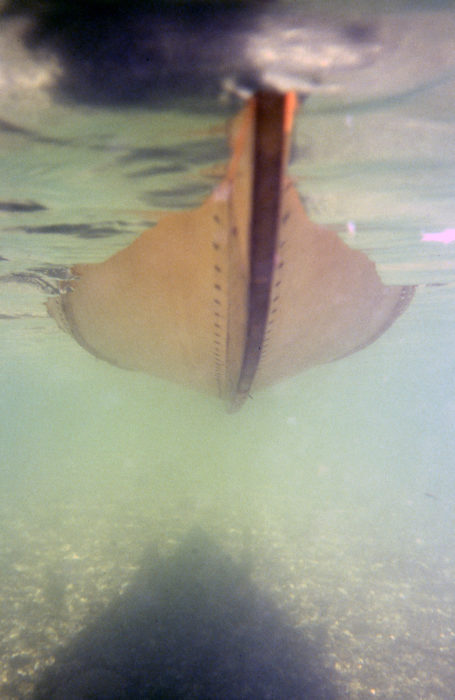

After leaving Ketchikan, we sailed north along Clarence Strait, a 4-mile wide passage between the mainland and Prince of Wales Island. While I’d made the traditional side-hung rudder for the faering, it was easier to steer with an oar. The rudder tended to loosen the ropes that held it in place and the transverse tiller, which would be behind me, was awkward to hold.

The side-hung rudder meant for the Gokstad faering creates a bit of drag that would turn the boat to starboard if not for the blade’s asymmetrical cross section, which creates a bit of port-turning lift. The rudder was effective, but because we frequently switched between sailing and rowing, we rarely used it.

Tongass Narrows dropped us in Clarence Strait where we picked up a strong wind out of the southwest. We set the square sail and reached crossed the 6-mile-wide mouth of Behm Canal. The sail occasionally got backwinded and when it popped back with a loud whump, Cindy would look at me with eyes open wide. The wind died when we finished the crossing at Caamano Point, so we dropped the sail and rowed for a while along the mainland side of Clarence Strait. When the wind picked up, from the south this time, we set sail again. The following seas built quickly and we were soon surfing at speeds we hadn’t experienced before. We could ease the sheets to keep from being overpowered, but that did nothing to reduce the sail area aloft and if the bow veered, the sail, stretched wide along the yard, would pull at the masthead and roll a rail uncomfortably close to the water. We dropped the sail, rolled it up around its yard and tucked it out of the way.

On our way to Meyers Chuck we had a fresh following breeze, too much wind for the square sail, so we set the tarp as a spinnaker. The photo was taken by some friends we made along the way who were traveling north in a cruising trawler. Many of the motor cruisers tended to stay for long periods in anchorages and harbors, so we regularly caught up with them.

Cindy threaded the halyard through the webbing loops on one end of our nylon tarp and tied sheets on the opposite corners. As a makeshift spinnaker it provided all the power we needed, and with the sail area down low we had a much more comfortable ride. The southerly carried us about 19 miles to Meyers Chuck. Cindy was at the helm as we sailed into the cove there, skimming over shoals at the entry in less than 2′ of water.

We spent the night at Meyers Chuck and woke to a thick fog. With time on our hands, we rowed into town, if a store and a post office that serve a few dozen residents could be called that. We stocked up on cookies and gingerbread, and rowed along the shore where most of the houses were perched on pilings either above the water or on the steep rocky slopes. It was past noon when the fog lifted; we rowed 2 miles along Clarence Strait, turned east into Ernest Sound and followed the ragged south shore of Etolin Island to Canoe Pass. The 9-mile-long channel between Etolin and Brownson Island funneled down from nearly a mile wide at its mouth to less than 80 yards in its northern third.

We enjoyed being in well protected water with the shoreline close by to make the scenery interesting, but horse flies found us and made a nuisance of themselves. They were a big as pinto beans and had a painful bite. We couldn’t outrun them so we had to fight back. I’d wave them off my arms and neck, but used the tops of my thighs as bait. I’d let them settle and prepare to cut into my skin and then sneak a hand up from the side and smack them from behind. Between the two of us, Cindy and I had 16 kills. We flicked the bodies overboard.

We anchored at the north end of Canoe Pass and on our second day rowing along Etolin, the skies cleared early in the day and the sun beat down on us. There wasn’t a breath of wind to cool us and the rowing was miserably hot. We found a small cove guarded by an islet at its mouth and fed with a small stream at its back. We filled our black water bag with fresh water for rinsing off, dropped anchor in the middle of the cove, and slipped over the side for a swim.

On an oppressively hot day of rowing around the east coast of Etolin Island, we ducked into a little cove for a refreshing swim and an opportunity to inspect the faering’s bottom.

After around 800 miles of cruising, ROWENA was in very good shape. We had taken great care whenever we brought the faering ashore and the varnished hull was still undamaged.

The varnish was in good shape but I was surprised to see that barnacles had made their homes in the decorative grooves on the plank edges.

I dove under ROWENA and noticed that barnacles were growing on the varnish below the waterline. They were tiny and easy to scrape off with my thumbnail. Back aboard the boat we rinsed with warm fresh water, pumped the bilge out, and left the cove to continue north to an overnight stop in Whaletail Cove.

Two powerboats came into Whaletail Cove after us, checked some crab traps, and left as quickly as they came. We had the cove to ourselves for the night.

We put an early end to the day’s rowing and settled in for a quiet evening and night in the cove.

We got a fast, if brief, ride north from Whaletail with wind and tide in our favor. We sailed 8 miles before the wind died and we had to row the last 12 miles to Wrangell.

After a stop for pizza and an overnight stay in Wrangell, we headed for the islands at the mouth of the Stikine River. We had been warned to avoid the broad mudflats that surrounded the islands, but the mud turned out to be more entertaining than hazardous. We had arrived on a rising tide, so we wouldn’t get stranded, and the mud was firm enough to support our weight when we stepped out of the boat. The thin layer of creamy fine mud on top was slick as grease. Barefoot, I could dig my toes in and run, and when I got up some speed I could jump, land on both feet and slide for about 20 yards. It was like skim boarding but without the board.

The silt deposited by the Stikine River was quite fine and and slippery, but wasn’t so soft that we couldn’t get out of the boat to stretch our legs.

We didn’t stay long because we were eager to get to LeConte Bay where we expected to find a glacier and icebergs. The mouth of the bay was five miles away and while we didn’t see any ice when we arrived there, we could feel the river of cold air flowing out between the banks. A mile in, we found icebergs, and they grew more numerous as we went farther in; the flood tide had been pushed them all back toward the glacier.

The glacier gave the inlet its own climate, cold and windy, while the weather elsewhere was warm and calm. The front of the glacier was about a mile wide and booming now and then as the ice cracked. In the years following our visit, Le Conte glacier retreated a mile from where is it here.

The bay followed a serpentine path and we didn’t get a view of the glacier itself until we were five miles in. At that point we were surrounded by ‘bergs, none of them much bigger than the boat, and most of them nearly transparent, having been melting in the sun. Closer to the glacier they were much larger, white and streaked with a Windex-like blue. One of the larger ‘bergs broke apart and the sound of the ice fracturing and the water pouring off it as it rolled echoed across the bay. The flow of cold air was kicking up a chop and was strong enough that we set sail and let it push us back out to Frederick Sound. The sun had dropped behind the mountain range that surrounded us and the shadow that swept across the ‘bergs and the glacier robbed them of their color, turning them a dusty gray. The tide had turned and many of the icebergs were now drifting out in the Sound.

The cold air sliding down the slope of the glacier created a sailing breeze on our way out of LeConte Bay.

It was late in the day and we needed to find a place to spend the night. We dropped the anchor in a small cove just to the north of the entrance to LeConte Bay. As Cindy got the stove out and started dinner—miso soup with potatoes, carrots, and cabbage—an iceberg a bit larger than ROWENA drifted by just 15′ away and came to a stop. It had grounded itself and now the tide that had carried it here was swirling around it. I pulled the anchor up and rowed us closer to shore. The ‘berg broke in half and the two pieces followed us. We had to leave.

Cindy kept cooking as I began the 7-mile row across Frederick Sound. We ate along the way and then rowed together in the dark under a moonless overcast sky for the last couple of miles. At Mitkof Island we entered a half-mile wide bay, more open than any place else we’d anchored, but it would have to do. I sounded with the anchor until I found about 20′ of water and then set it.

We had ideal conditions on Frederick Sound for our morning row to Petersburg. We could see Devils Thumb, a distinctive spire beyond the Alaska Coast Range and just across the border in Canada. The aptly named Thumb is visible here in the distance, just to the right of center.

When we stopped in Petersburg the harbormaster didn’t charge us for moorage because we had no motor. It rained all night but we were quite dry under the canopy.

After a 15-mile row to the north end of Mitkof, we took a day off in Petersburg before rowing north to Farragut Bay. We’d rowed 25 miles to get there and fought against a strong flood tide for much of the day, working the back eddies when we could, and making several sprints around points where rowing flat-out gained only a few inches per stroke. We arrived at Farragut tired. By the time we found an anchorage on the east side of Read Island, a two-mile long wooded island that lies just inside the mouth of the Bay, it was raining, and then we were tired and wet.

Crossing Farragut Bay in the fog kept us on alert, listening for fishing boats and looking for land.

We were enveloped in fog the next morning. We decided to row the 3-1/2 miles across the mouth the bay and set our course to err on the side of making land inside the bay rather than straying out into Frederick Sound. We had rowed for a long time in the murk and I was just beginning to get worried when we saw the dark shadow of land ahead. We turned south and followed the shore for 12 miles until we reached Cape Fanshaw. There fog lifted and we rowed another 4 miles and stopped for the night in a cove behind Whitney Island.

This little cove would have been the most beautiful and comfortable campsite of the entire trip, but we arrived in a flat calm that offered a quick, safe transit of Stephens Passage.

Our plan for the following day was to get in position to make the 8- to 10-mile crossing of Stephens Passage to Admiralty Island. We rowed north about 15 miles and found a cove that would put us in good position for an early start the next day. The white gravel beach allowed us to pull ROWENA ashore; the spruce trees surrounding it were draped with Spanish moss, there was a flat mossy place for the tent, there were no bugs—it was the best camp site we had found in Alaska. But Stephens Passage was glassy and absolutely windless. We looked north and south and there wasn’t so much as a cat’s paw anywhere.

Unusually calm conditions gave us an opportunity to make a quick afternoon crossing to Admiralty Island.

It was 5:20 p.m.; we’d be across in a couple of hours with daylight to spare. We shoved off and made a beeline for the south end of the Glass Peninsula, settling into a fast, steady pace. Even moving at a good clip, ROWENA hardly left a wake behind us. We made the crossing in 1 hour and 40 minutes. We rowed another 3 miles north along the west side of the peninsula and anchored in Blackjack Cove. The following day we rowed and sailed 24 miles up Seymour Canal to Pack Creek where we hoped to meet Stan Price, the man we’d heard about who lived with grizzly bears.

A fair wind gave us a chance to relax as we headed north up the 40-mile long Seymour Canal. The tiller extension and an oar serve as whisker poles to get the most out of the sail. My waterproof camera, strapped to a raft of inflatable fenders, snapped this picture with its timer.

Cindy took advantage of sailing up Seymour and napped in the shade of the main; I busied myself with raising more sail when the wind weakened.

We landed at Pack Creek that afternoon and found Stan at home in a shore-side cabin he’d built on a raft of logs to float it during especially high tides. He invited us in and Cindy took a chair by the door and I sat at his table. The walls were wide planks of rough-sawn lumber, the gaps stuffed with tissue paper and wrappers to keep breezes out.

Stan built his home on a log raft that floated at high tide in the backwaters adjacent to Pack Creek. Stan died in 1989 and little remains of his home. The area is now the Stan Price State Wildlife Sanctuary.

Stan was 87 years old but still had a full head of hair, bright eyes, and a quick smile. We asked about the danger of the brown bears that we had seen feeding on salmon in the creek. He said they had plenty of food and posed no threat to people. He added that might might attract some unwanted attention from the bears if we’d been cooking over a campfire and walking around, “smelling like a Big Mac.”

Stan Price was 87 years old when we visited him and he had been living at Pack Creek for 42 years. He told us about working in his younger years in the silver mines in Virginia City, Nevada, where the camp cook served antelope meat for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

We had been chatting with Stan for about an hour and a half when an enormous brown head poked through the door right at Cindy’s shoulder, then turned to look at me, sweeping its snout right over her lap. Cindy froze, eyes wide; Stan grinned and said, “That’s Lucy.”

Lucy, the bear who had poked her head in while we were visiting Stan, took a dip in the rising waters by his cabin. She was probably looking for salmon.

We spent the night at nearby Windfall Island and in the morning rowed under a cloudy sky past Swan Island. We rounded its northern end and the skies cleared as we entered the upper reaches of Seymour Canal. The air was still and warm and the water serenely still. To the east, cottony cumulous clouds rose above the mainland; the steep, thickly wooded hills to the north and west of us were edged with grey bands of bare rock at the water’s edge.

A break in the weather made for very pleasant rowing as we headed north from Pack Creek. Here in the middle of Seymour Canal I used the mast as a floating monopod for the camera.

We didn’t have many photos of ourselves rowing, and the setting deserved to be preserved on film. I had a camera equipped with radio-controlled shutter, so I just needed a place to put my camera in the middle of the canal. I tied the anchor chain to the top of the mast and slipped both carefully over the side. The mast had just enough buoyancy to support the weight of the chain and float vertically with its heel about 4′ above the water. I taped my non-waterproof SLR camera and the attached remote receiver to the mast and Cindy and I rowed around it, triggering the shutter with the transmitter.

The “selfie stick” for the previous photo was ROWENA’s mast with the anchor chain tied to the masthead to get it to float vertically and the rowing rudder lashed at the waterline to keep the camera steadily pointed in one direction. The antenna for the radio-controlled shutter is visible just to the right of the mast.

We had heard about a railway portage across the narrow neck of land that connects the slender, 43-mile long Glass Peninsula to Admiralty Island but didn’t know if it we’d find it in useable condition. It had been built in the 1950s by members of the Juneau Territorial Sportsmen’s association using rails and trams from old gold-mining operations. The latest we’d heard was that it had been rebuilt a few years ago.

As we paddled across the shallows to the mouth of the stream leading to the rail portage, salmon whipped up the still water.

The flood tide pushed us along toward the dead end at the farthest northern reach of the canal. To the west, a 25′-tall waterfall fanned out like a veil over a large rock in the middle of the falls. We were two hours ahead of the high tide and there was a broad expanse of muddy tidal flats separating us from the tall grass that surrounded a creek that we believed led to the portage. I took the anchor rode and two other lines, tied them together and to ROWENA’s painter, and we got out of the boat to wade closer to shore. Our rubber boots stirring up black mud; the air was foul with the odor of decay. I made the line fast to a large rock at the top of the flats and we headed to the creek, crossing a trail of 6″-wide bear-paw prints on our way.

We tried hauling the boat up one creek looking for the portage. I kept an eye out for salmon and gave them time to get out of the way. This turned out to be the wrong creek and we had to back ROWENA back into deeper water.

The first creek we tried was so full of salmon that we had to pick our steps slowly and carefully to avoid stepping on them. Some had made depressions in the gravel, exposing circles of light gray sand. Some of the fish had patches of grey and white on their backs. The dead fish that were completely white. We later found the right creek. It had a cabin about 150 yards from the tide flats and the cart was parked a few yards from the end of the rails, saving us a walk to the other end of the portage to retrieve it.

The rain came down in earnest as we started the first of several trips to get all of our gear to the railhead.

The creek we had to ascend was only a couple of feet wide and half as deep for much of its length, so we wouldn’t be able to float ROWENA up to the rails even at the peak of the high tide. We had to haul all of our gear to the railhead before dragging the lightened faering up the creek.

The direct path from the boat to the railhead was through shoulder-high grass, and we feared we might startle a bear hidden there.

When we got back to the boat to carry the first load, the tide was already up to the rock I’d tied the extended painter to. We coasted ROWENA to the channel leading up to the creek and pulled her up to the edge of the grass and set the anchor upstream. The clouds had been closing in above us, and it had started to drizzle as we were about to make the first carry to the railhead. We put on our rain gear and took the quickest route to the cabin, straight through the shoulder-high grass. We were both nervous about being in bear country near a stream teeming with salmon, walking through grass tall enough to conceal a bear.

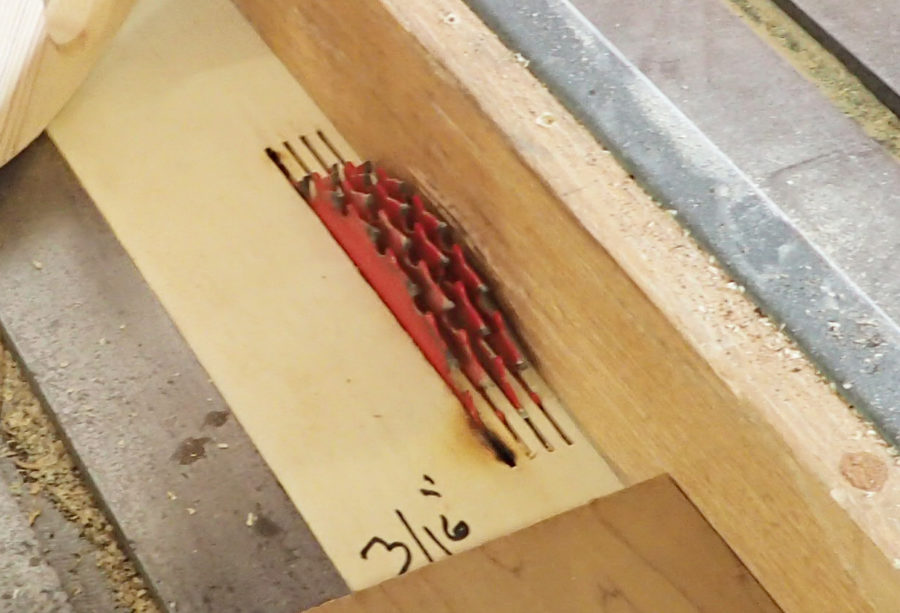

We kept ROWENA upright so that only the keel came in contact with the rocks. Its ironbark shoe could take the wear and tear.

When we picked up the second load, it began to rain hard and stayed that way for the rest of the hauls. With ROWENA empty, we dragged her to the creek and often skidded her keel across the mast partner and a 2×6 we’d brought from the cabin to keep her off the rocks. Salmon thrashed upstream as we approached. We cleared rocks that were tall enough to reach past ROWENA’s keel and scratch her garboard. Those rocks were easy to identify, even underwater, because they had silvery tips where aluminum skiffs had left their marks.

The farther up the creek we got the shallower and narrower it became. Hauling the boat over the grass was often less work.

After the long haul up the shallow creek, we had to lift the faering onto the rail cart.

When we reached the end of the rails, I brought the cart down and we eased ROWENA up on it and leveled her with two large fenders that we found by the cabin. It was about 5:00 p.m. and we didn’t have much daylight, so we quickly piled gear in and around the boat.

With the boat and gear loaded on the cart we could begin the 3/4-mile push to Oliver Inlet.

The cart scooted along nicely on the level stretches of track but the combined weight of the cart, boat, and gear made the uphill stretches hard work.

On level stretches, the cart rolled easily.

The rails took a turn to the right and took us into the woods, then ascended a hill. I pushed the cart uphill until it came to a stop and then put shoulder into it and braced my feet against one of the ties. Cindy chocked the wheels with a piece of 2×6, I took break, and then the two of us shoved the cart to the top of the rise. The effort left us panting and sweating. The rails leveled out across a broad area of muskeg, a patchwork of mossy hummocks and irregular pools of tea-brown water, dotted with crooked head-high trees. The tracks then tilted down toward a small valley and the cart picked up speed. I trotted along behind it, crossed a small trestle bridge and held the cart when it came to a stop on the uphill slope on the other side. When Cindy caught up we pushed it up to the next level stretch.

The longest stretch of rail took us across a soggy muskeg field. The boardwalk between the rails was wet, mossy, and very slippery.

We came to another valley and brought the cart to a stop to check on the tracks ahead. Everything seemed in good shape so we continued, letting the cart coast downhill, trying to keep its speed in check. I was having trouble keeping my footing on the wet planks that were set across the ties as a boardwalk, so I planted shifted to walking on the ties, pushing hard against them to slow the cart. It was no use. The cart continued to pick up speed and I had to choose between risking a broken leg and letting ROWENA fend for herself.

I released my grip and the cart raced ahead of me down the slope toward a second bridge and careened up the other side. As I ran across the bridge I could see the cart slow down and in an instant I realized I had to get to it before it started to roll back toward me or I’d have to jump off the bridge to avoid getting mowed down. I sprinted up the hill and caught the cart just as it came to a stop. I put my shoulder against it, planted my feet on one tie, held on to another with my hands, and waited for Cindy. Together we got the cart up to the top of the rise.

The last stretch of the portage descended a steep slope to Oliver Inlet. While Cindy tends our anchor rode as a belay to back up the cable winch, she waves mosquitoes away from her face.

We reached the north end of the portage where the rails take a turn and a steep drop to Oliver Inlet. A rusty cable winch anchored to a stack of ties was there to ease the cart down to the water. I had my doubts about the winch, so I tied the 110′ anchor rode to the cart and looped it around the end of a railroad a tie so Cindy could use it as a backup belay. As the cart rolled down the slope, I braked with the winch, slowing the descent until Cindy was at the tail end of the rode. I squeezed the brake tight and stopped paying out cable. Cindy walked down to the cart and set the rode up again with a turn around another tie close to the cart. It took us three pitches of the rode to get ROWENA to the end of the tracks. The tide was too low to float the boat off so we had to empty it before sliding it off the cart.

The end of the line brought us down to the tide flats of Oliver Inlet.

The air was thick with mosquitos and we batted them away as we spread a tarp out on the marsh grass and unloaded our gear on it. Cindy found our bug repellent; we slathered our faces and hands with it. We finally slipped ROWENA into the water. Cindy packed our gear while I winched the cart back up to the top of the hill.

It had stopped raining and it was hot and very muggy, but the bugs were so thick that we kept wrapped up in our rain gear.

When we finally took to the oars, a cloud of mosquitos followed us out from shore. There wasn’t a breath of wind, so we sprinted to create a bit of our own then ducked down to let the air sweep over us. We sprinted and ducked a half dozen times until we had left the swarm behind.

In the last of the daylight we sprinted away from the portage to escape the mosquitoes.

It had stopped raining, but the still air was thick with humidity, and we were drenched with sweat. We dropped the anchor in a small cove on the east side of the inlet, raised the canopy and made the cockpit ready for a late dinner of beef stew, couscous, and hummus. By the time we turned in it was 10:30, a very late night for us.

In the morning there were mosquitos all over the inside of the canopy; I smeared them with my thumb into the weave of the fabric while I waited for Cindy to wake up. We put the cockpit in order, took the canopy down, and did another sprint-and-duck session to leave the new crop of bugs behind.

We reached the mouth of Oliver inlet and could see a fog-aproned Douglas Island a little over 3 miles away across Stephens Passage. The sky was bright white with a high overcast; both air and water were still, perfect for the crossing. We took the shortest route across and by the time we reached Douglas, the fog had lifted. We rowed east to loop around the southern tip of the island into Gastineau Channel. Two fishing boats were on their way out of the channel and took a course that would take them across our bow. I was annoyed that we’d have to get tossed about by their steep wake, but then both turned to go astern of us. As they passed,a blond man at the helm of the second boat called out, “Chris, is that you?”

“Paul?” I replied. It was a friend of mine from Seattle. He brought his boat SUPREME, alongside. Apparently one of his deck hands had spotted us and reported to Paul that he’d seen “two Indians in a war canoe.” The two boats had altered course to take a closer look.

Paul Enquist, a friend from Seattle and an oarsman coached by my father, found us crossing Stephens Passage on our way to Juneau.

Paul had his cook bring up raspberry Danish and apples from the galley. We said our goodbyes and SUPREME motored off while we took turns eating our unexpected breakfast. Even with just one of us at the oars we made good progress along the steep brush-covered flanks of Douglas Island, streaked white with waterfalls.

Eight miles of Gastineau Channel were all that separated us from Juneau. SOBRE LAS OLAS, a 1929 motoryacht we crossed paths with weeks earlier, came up astern and when she was abeam a half mile to the east of us gave two blasts of her horn; the echoes bounced off the walls of the channel.

Our summer aboard ROWENA put us in good shape and in good spirits.

We reached Juneau in 54 days, having covered over 1000 miles, mostly by oar, a fair bit under sail, and a tiny stretch by railroad. Cindy and I returned to Seattle from Juneau aboard an Alaska State ferry with ROWENA riding on the car deck tucked under a semi’s trailer.![]()

Part 1 of this story appeared in the March issue.

Epilogue

ROWENA took a well-deserved break in the lobby of a bank serving the largely Scandinavian community of Ballard, a neighborhood in northwest Seattle.

We sold the boat to my father to help finance a move to Washington, D.C., where Cindy had won an internship at the Library of Congress; I found work at the Smithsonian Institution. We later moved back to Seattle when I was offered the editorship of Sea Kayaker magazine. ROWENA was purchased by a family friend in Douglas, Alaska, right across Gastineau Channel from Juneau, and was shipped north again. Cindy and I raised a son and a daughter and went our separate ways in 2000. ROWENA’s owner moved to the Seattle area and the boat took yet another ride along the Inside Passage. The Gokstad faering proved itself to be a good sea boat and remains the most beautiful small boat I’ve ever seen.

Christopher Cunningham is the editor of Small Boats Monthly.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small wooden boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Terrific story, Chris, simply told.

Thank you!

Thanks for sharing your honeymoon with us, so we all could enjoy it too. You have a great memory, or you kept good notes.

Fantastic story. This made for great reading early in the morning before making some business calls and texts. Being in my own business makes for little extended time to do something like this. But I have set up a bucket list of places I want to row EMPTY POCKETS, my newly refinished Seaford Skiff.

Hi Chris

I’ve just spent the afternoon reading Pt 1 and Pt 2 of your trip . Fascinating , I kept on crosschecking your route with Google maps. What a wonderful adventure.

I too want to build a faering, my favorite at the moment is Lillebror, built from timber left over from the build of Dragon Harald Fairhair.

Many Thanks

Peter Simpson

Thanks for both this and the earlier Inside Passage story. Nice voyages and accounts.

Eric

A shame the year is not mentioned. Otherwise, a GREAT! morning read before getting the day under way!

I’m glad you enjoyed the article. The cruise was taken in the summer of 1987 and I’ve added the year in the text above. The date had been noted in Part 1 of the story. If you haven’t read that first installment, it might make for another good morning read.