"Sweet lines” is often the first thing out of the mouth of classic-boat aficionados having a first look at an Abaco dinghy. It’s no wonder legend has it that this traditional Bahamian workboat had a role in inspiring Capt. Nat Herreshoff’s famous 12 1/2 daysailer. Dinghy owners call them little jewels and will lavish hundreds of hours and many thousands of dollars on full restorations.

During the mid-20th century, yachtsmen began gravitating to the Sea of Abaco in the Bahamas. Lying between the Abaco Cays—Green Turtle, Great Guana, Scotland, Man-O-War, and Elbow—to the east and Great Abaco Island to the west, the Sea makes a sheltered cruising ground. Visitors found friendly islanders with accents like Cornish fishermen, clear blue water rife with reef fish, and good breezes. They also found a vibrant wooden boat building industry on Man-O-War Cay and in Hope Town on Elbow Cay. The yachtsmen and expats proved a ready market for local workboats to be used as daysailers and racers.

Nobody knows for sure when the first Abaco dinghy was built, or who built it, but the type has been around as a small fishing boat since the late 1800s. Dinghies are traditionally either 12′ or 14′ overall, with a 5′ beam and a 2′ draft. During the middle decades of the 20th century Abaco boatbuilders like Maurice Albury on Man-O-War Cay and Winer Malone at Hope Town launched hundreds of dinghies for fishing, daysailing, and racing. Some builders had government contracts to turn out dinghies to supply the Bahamian fishing fleet.

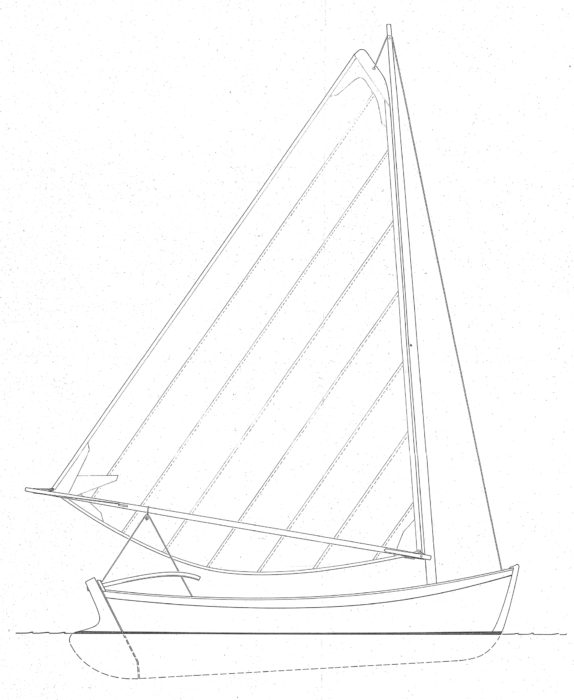

An Abaco dinghy carries a catboat rig on an unstayed mast. The large three-sided sail (about 200 sq ft) has a nearly straight leech and a long, loose foot with a deep roach. The sail’s large headboard, known locally has a “banana board,” can be adjusted to tension the leech for different wind conditions. Sails were traditionally cotton, but today they are Dacron or Oceanus sailcloth. Hope Town–built boats are fully open; many Man-O-War boats have the bow decked over to just aft of the mast partners. The dinghies usually have a notch in the transom for a sculling oar.

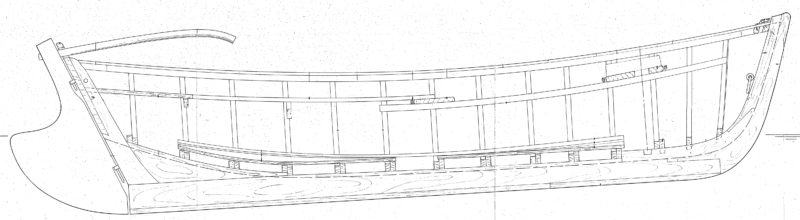

With their carvel plank-on-frame construction, full keels, and wineglass transoms, Abaco dinghies are more like little ships or scaled-down versions of the bigger Abaco fishing smacks than actual dinghies for harbor transport or towing behind yachts. Like bigger Bahamian smacks and sloops, Abaco dinghies are built without plans from the keel up by what local builders often refer to as “mother’s wit.” Boatwrights work from a traditional formula. The beam is half the keel length. The transom measures three-fourths of the beam. Mast height is twice the length of the keel. Abaco dinghies have subtly curved stems; they’re raked on Man-O-War boats and nearly plumb on Hope Town boats. Abaco dinghies have a graceful sheer, low freeboard, and keels with moderate drag. The greatest beam is slightly forward of amidships.

To begin construction, builders lay a keel and attach a stem, a sternpost, and a transom. Then they construct a mold or use one handed down over generations for the center rising-frame. Many builders add a forward frame and a stern frame, too. These three frames are connected by ribbands to the stem and transom. Once the ribbands outline the shape of the new hull, the rest of the frames can be hand-cut to fit before the hull is planked.

photographs by Jay Fleming, jayflemingphotography.com

photographs by Jay Fleming, jayflemingphotography.comDANDY’s owner Dave Pahl hefts a bit of the locally grown corkwood that provides crooked timbers for sawn frames.

Planks are 3/8″ to 7/16″ thick. Builders use natural crooks shaped with hand tools for frames. These frames are 1″ wide with varying depth and are set on 12″ to 15″ centers. Traditionally, builders used local mahogany they called madeira or madera (Portuguese and Spanish for timber) for framing crooks, but in more recent years they have used corkwood. Planking, gunwales, and decking are either cypress or Caribbean pine. To season the lumber, boatwrights soak it in the harbor for six months. In the past, builders used iron boat nails and brass screws. Restorations use bronze. Getting the planks to make the sharp twist running aft into the wineglass stern is not for the novice builder. Similarly, shaping the garboards and the planks at the sharp turn of the bilge requires advanced boatbuilding skills.

A few decades ago the demand for dinghies fell sharply. Abaco fishermen had turned to speedy fiberglass runabouts, and easily available wood began to disappear. Few orders came to the builders and aging boats began disappearing, but fortunately, Hope Town cherishes its strong maritime and sailing tradition and booms as a mecca for cruising yachts. Here, with the support of the active Hope Town Sailing Club, local lovers of traditional Bahamian small craft have been reviving the fleet of dinghies. In the U.S., boatbuilding programs like The Apprenticeshop in Maine began teaching a new generation of boatwrights how to build and sail the Abaco dinghy.

These days, people go to great lengths to get an Abaco dinghy. After searching for years for a dinghy of their own, Dave and Carol Pahl, “snowbirds” with a winter home in Hope Town, rescued one from a Hobie Cat dealer in New York. Following a couple of years of stripping and refastening it in the U.S., the Pahls shipped their boat to Hope Town at considerable expense. They finished the restoration and launched the 14′ DANDY this winter.

Sculling is common in the Bahamas and the Abaco skiffs often have sculling notches in the transom instead of oarlocks or tholes on the gunwales. The notches are set to port and the sculling is done left handed, freeing the right hand for other tasks.

I had a chance to sail DANDY one blustery February morning in Hope Town Harbour when Dave said, “Go have fun.” With the wind veering through 50 degrees and ranging from flat calm to 18-knot puffs, I had great conditions for getting to know DANDY. Leaving the dock in virtually no breeze, I sat on the floorboards and waited to see if this vessel would move. To my delight her big, deep-bellied sail filled with wind I could barely feel, and we slipped out into the harbor on a dead run.

Howard Chapelle notes “The Bahama sail is always made long on the foot and not excessively lofty. This, with the heavy roach at the foot, brings the center of effort low by modern standards for a triangular sail.”

As soon as we found clear air, the wind suddenly blew 12–15 knots. DANDY charged forward with noticeable acceleration. We took a gust as I was putting her on a close reach and the boat heeled over abruptly. With DANDY’s long boom, there’s a lot of sheet to manage, and I was slow at trimming. The end of the boom and the clew of the sail dragged in the water before I could trim in or adjust my weight to windward. As I got things under control, I reminded myself that DANDY’s round bilges and relatively narrow beam made her tender. In these blustery conditions, having a second person in the boat as ballast and a sheet tender would definitely have been an asset.

How she screamed along on a reach! With small adjustments to the tiller, I let DANDY run a swift and easy slalom between the yachts in the mooring field. Hardening up onto a beat, I found that DANDY pointed like a typical 100-year-old workboat design. She didn’t like to go closer than 45 degrees to the wind. But even with dramatic shifts in the direction and intensity of the breeze, she held a pretty consistent 25 degrees of heel as long as I was quick to trim the sheet with the puffs and lulls. If I was the least bit slow to ease the sheet, DANDY could dip her lee rail and ship water. In these conditions with just one person aboard, she had a notable weather helm.

“Unstayed masts were sometimes looked upon as a safety factor, for it was thought that the bending of lofty masts spilled the wind out of the sails to some extent in a knockdown. In the Bahamas, the unstayed masts are thought to permit carrying sail longer, before reduction becomes necessary….” Howard Chapelle

I was exhilarated but busy . More than a few cruisers came topside on their boats to watch. Crews on motoryachts and runabouts stopped to look and take pictures as this sailing anachronism worked her magic. But I was too busy in the blustery conditions to bask in the glory. Her boom was only about a foot above the gunwale. The sail blocked my vision to leeward unless I lay with my shoulders against the windward rail so I could peep under the sail. Once again I wished that I had a shipmate, this time to act as a lookout.

I had heard that Abaco dinghies are hard to tack, but in the calm water of Hope Town Harbour, DANDY had no problem. With her full keel, she just required a firm shove on the tiller to bring her around. She did not come around fast, though. The sheet, hanging beneath the boom, tended to catch on the back of my head. With the big sail and unstayed rig, jibing has to be carefully controlled to be safe.

Growing bolder, I sailed out into the Sea of Abaco to see how DANDY would do in a hearty wind and choppy waves. She loved beating into the froth and was remarkably dry. In a beam sea she had an easy roll as long as I sheeted the boom in far enough to keep it from tripping in the waves. Clearly, DANDY’s type had been built to fish and travel in these conditions—but tacking her into this chop was no easy matter. Unless I fell off on a screaming reach and roll-tacked her like a modern racing dinghy, DANDY wanted to stall.

Ghosting back to the dock, I was still throbbing with adrenalin. While she would be an easy daysailer for a couple in winds less than 8 knots, in blustery conditions she was a thrill ride, and to sail her safely I needed to be on top of my game.

Abaco dinghies have long had a reputation for being good sailers in the strong tradewinds of the Bahamas.

With DANDY added to the fleet, Hope Town now has 14 Abaco dinghies sailing and racing. More restorations and new boats are in the offing. During my visit, I found a trio of folks under a harbor-side tent stripping paint from an old dinghy in preparation for a full restoration. Internet threads highlight a resurgence of interest in the type, too, among both modelers and amateur builders.

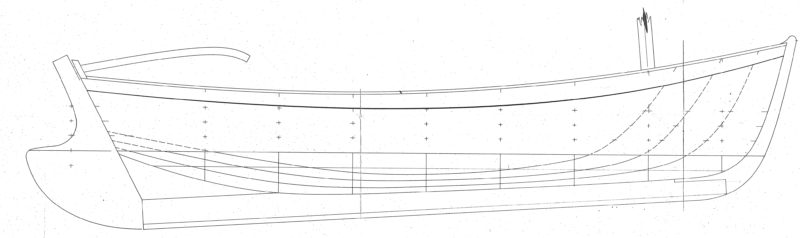

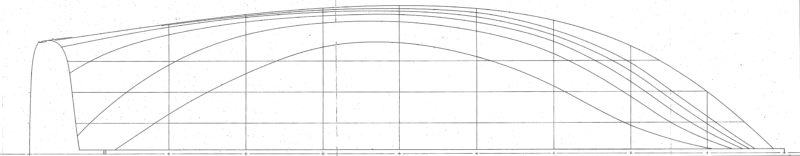

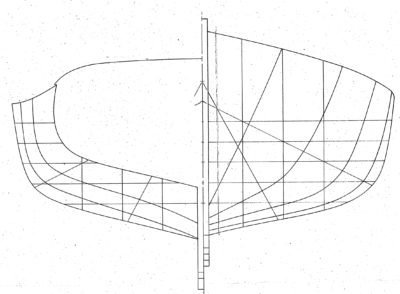

Local builders don’t use plans but lines drawings, offsets, and construction details are available from The Apprenticeshop. Construction is challenging, so if you want one of the Abaco boatwrights or the Apprenticeshop to make you a new dinghy, keep this in mind: Sweetness comes at a price.![]()

Randy Peffer is a frequent contributor to WoodenBoat, the captain of the research schooner SARAH ABBOT and a relentless racer and gunkholer in all manner of small craft from canoes to catboats.

Particulars

[table]

Length/12′ 3.25″

Beam/4′ 9.5″

Draft/1′ 4″

Sail area/93.5 sq ft

[/table]

(Dimensions above and the lines drawings below are from the plans offered by The Apprenticeshop. They represent an Abaco dinghy built by Maurice Albury on Man-O-War Cay in 1952, and measured by D.W. Dillion in 1985.)

For a new Bahamian-built dinghy (likely to be somewhere north of $20,000) contact:

Joe Albury, Joe’s Studio, Man-O-War Cay

Andy Albury, Albury’s Designs, Man-O-War Cay,

David Wright, Abaco Boat Restoration, Man-O-War Cay,

To bring an old dinghy into working condition contact:

Great Harbour Boat Restoration, Hope Town, Elbow Cay,

The Apprenticeshop in Rockland, Maine offers plans for $35 and can build an Abaco dinghy for around $10,000 to $25,000, depending on material selection and size—anywhere from 12′ to 20′. Address inquiries to Kevin Carney, Lead Instructor.

Howard Chapelle includes a description and drawings of what he calls a Bahama dinghy in American Small Sailing Craft. The 14′ 5 1/2″ boat was built at Hope Town in 1898.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!

My addiction to wooden boats, and this boat in particular, began at the age of 14 on my family’s first visit to Man-O-War Cay in the late 1960s. Each day I would go down to the waterfront shop of a local boat builder and watch him work on an Abaco Dinghy. I have admired these boats ever since.

I do not remember forward decking on the Man-O-War sailing dinghies. There was a powered variant with a small one-cylinder engine that had forward, aft, and side decking, but I never saw decking on a sail dinghy. The sculling oar is a special long, heavy oar, quite unlike a rowing oar, usually as long as or longer than the boat itself.

Our family maintained a house, boat, and numerous small boats there from 1950 through about 1970, and we love to return any time. A big disappointment is the smell of fiberglass when walking down main street.

If it pointed to 45 degrees, how did it foot?