I was paddling on a placid Royal River with my four-year-old son Noah kneeling in front of me on a wooden Tidal Roots stand-up-paddle (SUP) board. The water hissed quietly as it slipped under the bow. The peaceful scene was disrupted by a paddler yelling, “That is a gorgeous board!” While I’d heard praise like that more than once while using the Maine-built, bright-finished Tidal Roots board [The company is no longer in business.—Ed.] It’s not something I ever hear when I’m paddling my fiberglass-and-expanded-polystyrene-foam board made in China.

Tim Greenway

Tim GreenwayBookmatching the northern white cedar turns the variations in the wood’s grain and color into appealing patterns.

Kyle Schaefer and Kent Scovill of Tidal Roots make SUP boards in a weathered, three-bedroom house in Eliot, Maine. Both are avid fly fishermen, and four years ago, when a friend of Schaefer’s left a paddleboard with Kyle, they immediately used the board to give them a better way to find fish. A light went on: What if they designed an SUP board for stability rather than speed, one that was built in Maine out of local materials, and built it of wood? They set about designing their first standup paddleboard. Building it took “forever,” but paddling it for the first time, Kent recalls, “was the best day ever.” Kyle and Kent are now producing about 36 boards a year.

Work on a Tidal Roots board begins in an old barn—warmed by a wood stove—where wood is rough cut and planed. The house’s basement, their principal workshop, is 750 sq ft and cramped; their workshop tables, by necessity, are on casters. The day I dropped in on them, they were building a Shoal, an 11′6″ board, a refinement of their first board, thicker and with less rocker to the nose. Kent says it has less plow, more glide.

Peter Van Allen

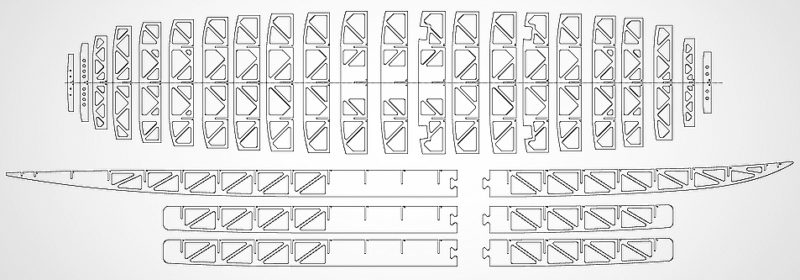

Peter Van AllenTidal Roots boards have between 24 and 28 CNC router-cut pieces in the framework. The solid balsa blocking to the left provides a backing for the recessed hand-grip installed later.

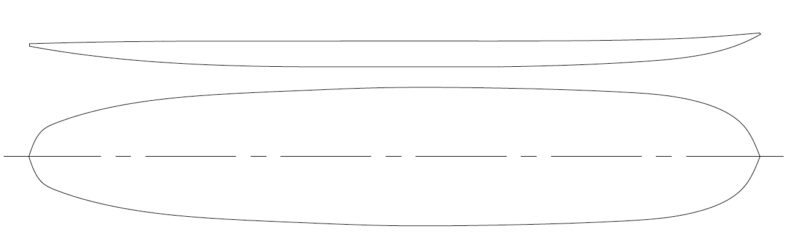

The Tidal Roots boards have a spar-and-rib interior framework like that of an airplane wing. The patterns for the interlocking pieces were designed on a CAD system by Jon Deschenes, a friend in Tennessee, and two shops—one in Dover, New Hampshire, and one in Amesbury, Massachusetts —cut the pieces from ¼″ marine-grade plywood using CNC machines. The boards’ exteriors are northern white cedar, and about 95 percent of it is supplied by Bruce Tweedie of Thorndike, Maine.

For the bottom and top of a board, Kyle and Kent edge-glue 3″ to 4″-wide book-matched boards of northern white cedar. The glued-up sheets start at ⅜″ and are taken down to a fat ¼″ with a 43″-wide thickness sander. The frame pieces are assembled with interlocking joints, and the builders glue balsa blocks to the spars and ribs where cuts will later be made for a fin box, a handhold, and several tie-down fittings.

With the bottom panel on the workbench, a chalkline is snapped down the center from nose to tail. Along the line they lay a template made of cardboard and edged roughly, it seems, in black duct tape. “We’re not building spaceships down here,” Kyle quips. The template’s precut notches show where the ribs will match up. They trace out where the ribs will be positioned and where adhesive caulking needs to be applied prior to assembly.

Peter Van Allen

Peter Van AllenAfter adhesive is applied and the framework sandwiched between the top and bottom panels, a two-part press (the bottom shown here) gives the board its shape.

The top and bottom panels and the plywood frame are all glued together at the same time. Kent and Kyle place the marked bottom panel on a purpose-made press that will join and mold the bottom, framework, and top. They squirt on a sub-floor adhesive on the bottom panel and then lay the spar-and-rib assembly on top of that; more adhesive is applied to join the top panel. The top of the press is put over all and the press halves are drawn together with bar clamps, bringing the top and bottom panels to their curved shapes against the interior framework.

“Rail strips” made of straight-grained western red cedar are bent along the panels from nose to tail and serve as chine logs and sheer clamps. The sides, or rails, of the paddleboard add substantially to the labor of the board: northern white cedar “rail blocks,” roughly 1½″ wide are applied vertically one at a time, side by side.

To trim the ends of the board for the nose and tail blocks, Kent uses a Festool track saw, a circular saw with an integral guide. The nose block’s stock is northern white cedar sandwiched around western red cedar. It gets mitered and epoxied to the angled forward end of the board. The Shoal’s straight tail block has the same laminated wood structure. Once the epoxy has set, Kent uses a power planer to get the approximate shape, then a hand plane, and finally a sander.

The board is finished with fiberglass and epoxy. The ’glassing is done by Keith Natti of Twin Lights Surf Company in Gloucester, Massachusetts. They use a surf industry-inspired epoxy with a UV inhibitor built in. A pad is glued to the deck to keep the feet from slipping. Each board has a vent equipped with a waterproof/breathable membrane that allows the board to equalize atmospheric pressure and avoid damage when the board sits for an extended period; the vent is closed before the board hits the water.

Each Tidal Roots board has a conventional fiberglass fin, like those you’d see on conventional SUPs, set in in a fin box. A purist might want to have a ’glassed-on fin made of marine ply or laminated wood. Other deck fittings include anchor points for an ankle leash and equipment tie-downs, and twist-on adapters for RAM Mounts to hold GPS, camera, or fishing rod.

For do-it-yourselfers Tidal Roots offers kits that include spar-and-ribs parts, instructions, and recommendations for the tools and materials required. The long fore-and-aft spars have jigsaw-puzzle joints to allow them to be shipped in shorter sections.

Tim Greenway

Tim GreenwayA handhold at the board’s balance point makes carrying easy.

The Sand Bar model I tried is a 12′ board, the longest and fastest of the Tidal Roots models. It weighs 40 lbs; smaller Tidal Roots boards tip the scales at 38 lbs. Each Tidal Roots board is equipped with a handgrip that is well balanced and comfortable when toting the board from car to water.

The Sand Bar paddled smoothly on the flat water of the Royal River in Maine. At 28¾″ wide and 5″ thick, it’s stable enough to carry a small child just ahead of the paddler. I’m 170 lbs and my son adds another 40. The Sand Bar could just as easily carry 40 lbs of gear in dry bags for extended day trips and overnighters. The Sand Bar would be a stable platform for fishing or even yoga, though Tidal Roots’ Harbor Seal model, at 10′ x 33¾″ x 5¾″, is specifically designed for yoga.

Eager to get it into rougher conditions, I paddled on a windier day down the saltwater portion of the Royal River toward Casco Bay. Paddling into the wind is a challenge on any SUP, but the Sand Bar held its own. When a motorboat whizzed by, the board chugged right through the wake, easily rising and falling with the waves and feeling stable and controlled. While some would argue that the wood absorbs vibration and energy, I honestly didn’t see a huge difference going from foam-and-fiberglass to wood. I felt like the deck was more forgiving, which is easier on my old knees, but the hull is as stiff and strong as any board I’ve ridden.

With the stock fin from Futures Fins, the Sand Bar tracks well yet also turns easily. It’s not a speed machine, but it would be a comfortable board for a journey of several miles. Kyle reports that he’s paddled the Sand Bar 10 miles comfortably, and I think that if you’re used to extended trips, this board will get you there in comfort and with relative ease.

To duck out of the wind, I paddled the board into the tidal marsh, and it was there that the board excelled. I followed a tidal creek and the board turned easily with the bends in waterway where I was sheltered from the wind. Suddenly, some baitfish broke the surface, and I could now see the appeal for a fly-fishing paddler. It is indeed a gorgeous board, but its advantages are more than cosmetic. It’s durable, made with products that are sustainable, and will get you where you want to go—in style.![]()

Peter Van Allen is a fanatic for small craft that keep him close to the water, whether it’s a surf ski, a sea kayak, a paddleboard, or a single-fin surfboard. He is based in Yarmouth, Maine.

Sand Bar Particulars

′

Update: Tidal Roots is no longer in business. The article appears here as archival material—Ed.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Excellent article. I particularly like the finish on the SUP board; it has a beautiful quality to it.